African athletes captured many hearts at the Paris Olympics

But the continent will need much more than good vibes if it is to increase its medal count in 2028

Hollywood star Tom Cruise’s stuntastic rappel from atop the Stade de France in Paris was a most befitting way to end the 2024 Summer Olympics and hand over the flag to Los Angeles. The approximately 10,714 athletes who participated in the games put on a show for the billions of viewers worldwide who tuned in to see some of their favorite sportspeople.

Every four years, the Olympic Games feature miraculous displays of athletic marvel, shattered records, tears of joy, political statements, WTF moments and the crowning of national heroes.

On that score, Paris 2024 was no different. Yusuf Dikec, the Turkish medal-winning pistol shooter, was an instant hit on social media thanks to his relaxed, hands-in-pocket shooting posture that spawned numerous memes. You will not see many more dramatic conclusions to a championship event than the men’s 100-meter final, which was so close that the U.S.A.’s Noah Lyles — who won the gold medal — initially assumed that he had finished in second place and a photo still of the finish line was required to declare the winner of the contest.

Dutch runner Sifan Hassan wore a hijab to accept her gold medal in a powerful show of support for French Muslim athletes who were banned from wearing one during the games in Paris. And there was no bigger in-person fan than Snoop Dogg, who went from rapping with 2Pac in 1996 about “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted” to being an unaccredited U.S.A Olympics mascot 28 years later.

As a huge sports fan, the Olympics capped a fantastic year of my viewing of international sports competitions that began with the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) and included a summer of viewing Copa America and the European Football Championship concurrently.

I watched the Olympics with particular interest in the performance of the more than 1,000 athletes representing African nations. They made up an ensemble of over 50 African delegations that attended the opening ceremony on July 26, with the presidents of Cameroon, Senegal, Rwanda, Djibouti, Gabon and the Central African Republic making up the approximately 80 heads of state and government who were present for the festivities. The leaders were official guests of French President Emmanuel Macron and Thomas Bach, the president of the International Olympic Committee.

How Africans wowed global audiences in France

In Paris, the one city that can realistically challenge London’s claim to the unofficial title of the most “African” city in Europe, Africa left an ineradicable mark on the Olympics.

The French-Malian singer Aya Nakamura delivered an exciting musical performance in the opening ceremony. From Côte d'Ivoire, Tunisia, Zimbabwe and Rwanda to Togo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Algeria and Namibia, Africa’s diversity, cultural richness and flamboyance was displayed on the boats that ferried the national delegations down the River Seine during the parade of nations. For my money, Liberia’s athletes, who were clad in Telfar-designed black gowns with a neckline styled in the shape of the African continent, had the best get-up of the delegations. But the Nigerians, Burundians and Malians also held their own.

During the two weeks of the games, “Africa Station,” a fan zone located in Île-Saint-Denis in the northern suburbs of Paris, was a meeting point for Africans of all nationalities to enjoy the Olympics and the continent’s rich cultural traditions. The initiative, which was backed by the Association of National Olympic Committees of Africa (ANOCA) and held in partnership with La Maison de l’Afrique, held live broadcasts of Olympic events and presentations of medals to African athletes, concerts, art shows, meetings with athletes, exhibitions and cultural events. There was a food court, crafts from different African countries and a team of French-speaking African journalists at the station. Without question, Africa Station was a place to be if you were in Paris to catch the summer games.

The 2024 Olympics had many heartwarming moments involving African athletes. The South Sudan men’s basketball team, which nearly upset the U.S.A. in a thrilling exhibition game and defeated Puerto Rico in its maiden appearance at the Olympics, won the affection of millions with its exploits in Paris. Kaylia Nemour, who won the gold medal in the women’s uneven bars event, became the first Algerian and African gymnast to win an Olympic medal. Kenya’s Faith Kipyegon became the first person to win three consecutive gold medals in the women’s 1500-meters event, while setting a new Olympic record of 3 minutes and 51.29 seconds.

D’Tigress, the Nigeria women’s basketball team, made an impressive run to the quarterfinals before bowing out to the eventual gold medalists from the United States. D’Tigress is the first African squad — male or female — to advance to the last eight of Olympics basketball. Its charismatic coach, Rena Wakama, won the award for Best Coach.

And what about Letsile Tebogo, Botswana’s first-ever Olympic gold medalist who won the men’s 200-meters event and returned home to a hero’s welcome in Gaborone, the country’s capital?

Deja vu for Africa at the 2024 Olympics

Athletes from 12 African countries won a total of 39 medals — 13 gold, 12 silver and 14 bronze. This was an increase of two on the tally from the Tokyo games three years ago but six fewer than the record haul of 45 at Rio 2016. As in Tokyo, Kenyan athletes were Africa's most successful competitors at the Paris games with four gold medals and a total of 11 overall. The list of Africa’s most successful nations in 2024 mirrored that of the 2020 tournament, as Kenya, South Africa, Egypt and Ethiopia finished in the top five on both occasions.

The patchy performance of African athletes in Paris reignited debates about the state of sports administration across the continent. Issues of talent development, funding and infrastructure were the focus of discussion among African viewers, perhaps most intensely among Nigerians.

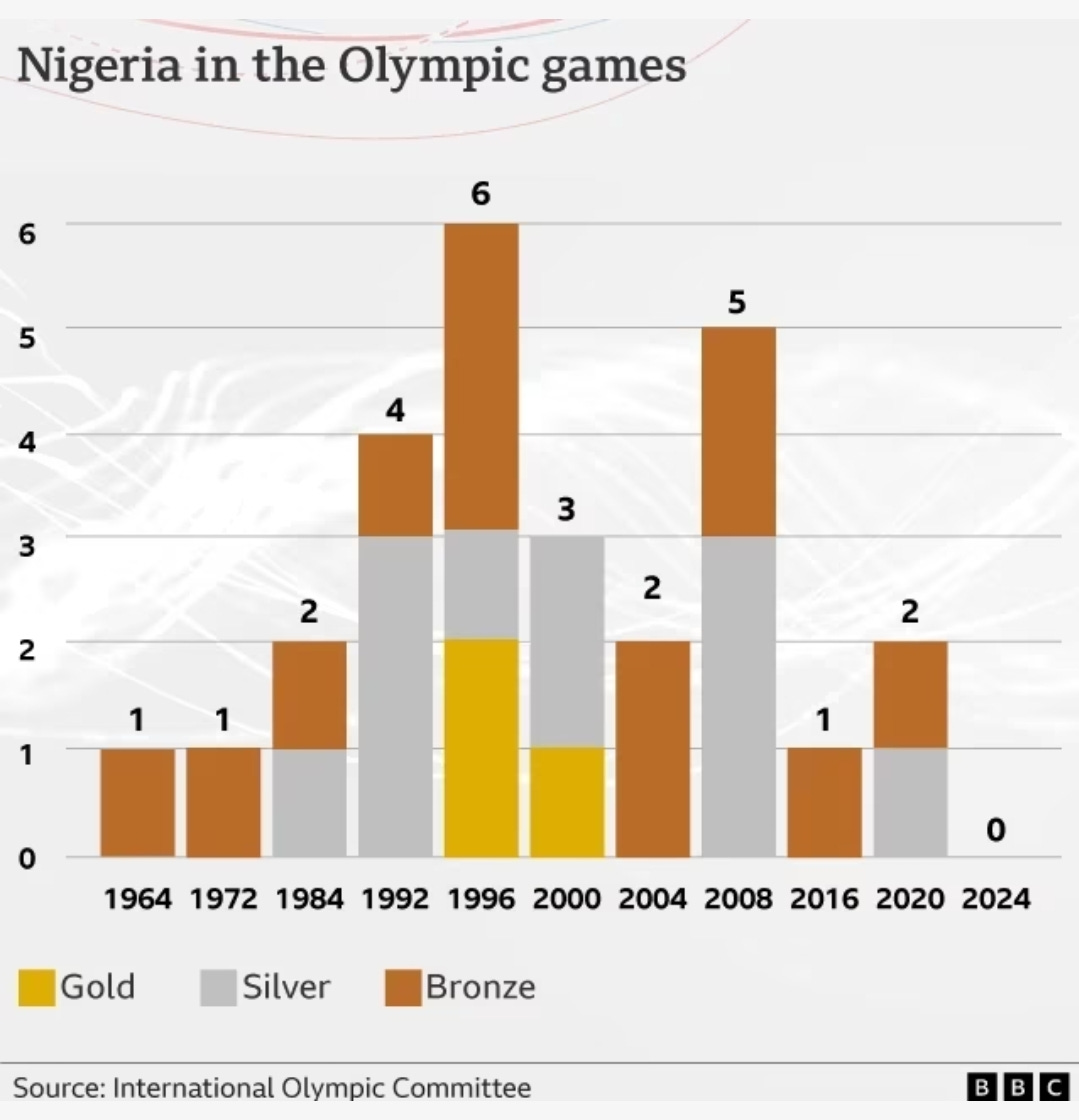

For the second time in the past four summer Olympics, no athlete representing Nigeria won a single medal in the 2024 Olympics. That this happened during a tournament in which at least eight athletes of Nigerian descent won medals representing other nations underscored the pervasive belief among the public that Nigeria’s competitors were let down by factors like a lack of adequate investment and incompetent sports administrators. They have a point, given that some of Nigeria’s Olympians paid their own way to Paris and one of the country’s top sprinters was inexplicably left off the entry list for the women’s 100-meter event.

The disappointing outcome of the Nigerian delegation’s participation in the 2024 games drew outrage in a country whose athletes have participated in the summer Olympics since 1952 and have won a total of 27 medals including gold in men's football and the women’s long jump at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Calls for the resignation and dismissal of top athletics figures reached a fever pitch that Nigeria’s under-fire sports minister felt compelled to defend himself and other senior officials in a televised interview earlier this week.

Even in Kenya, whose athletes performed much better than their counterparts from Nigeria and other African nations, many folks felt that the country's medalists achieved success in Paris despite what they considered to be an inadequate level of support from the national sports federation.

Some others argued that Kenya ought to nurture medalists in other activities aside from distance running, which Kenyan athletes have dominated for many decades. In South Africa, Ghana and traditional North African powerhouses like Egypt, Tunisia and Algeria, there was a palpable sense of disappointment among some fans who felt that their athletes did not perform as well as they could have.

These lamentations are not new or unique to the Olympics. They frequently emerge after other major international tournaments like AFCON and the World Cup. In a piece I wrote after the Tokyo games three years ago, many of the issues that came up this year in Paris were prominent then:

… The underperformance of athletes from continental giants like Nigeria, South Africa, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana and Kenya was noticeable, with some countries posting their lowest medal tallies in years.

The circumstances surrounding the underperformance of African athletes at the Games were just as frustrating. Ten Nigerian athletes were disqualified for failing to meet testing requirements under anti-doping rules. Athletes from Morocco, Ethiopia and Kenya were similarly disqualified. Nigeria’s gold-medal hope Blessing Okagbare was also banned for using an illegal substance, while the country’s failure to properly equip its 60 athletes across 10 sports for the 2020 Games may have cost it more than $50 million of sponsorship deals, leading to a round of finger-pointing among its sports authorities. South Africa’s 4×100-meter men’s team also disappointed when they dropped the baton in their relay race. Kenya’s 100-meter sprinter Mark Otieno was provisionally suspended for failing a drug test.

Fans back home and even some of the athletes pinned these disappointing outcomes on administrative oversights by national athletic associations. Almost immediately, calls for resignations of the officials responsible and a revamping of sports administration structures across various African countries began, among individuals, on social media and across domestic mainstream media. The familiar problems besetting sports organizations were listed, including but not limited to corruption, nepotism, low funding for sports and interference by political elites.

African sports federations must go back to some key basics

Invariably, many Africans argued that athletics should be removed from the state’s purview — sports federations on the continent are typically publicly managed — and placed in non-governmental hands. But as I noted in 2021, the state-vs-private-management debate is a false dichotomy that obscures the collaborative nature of sports administration in most countries.

It ignores structural shortcomings that sports federations must fix regardless of what management model they adopt, like the weakening of public education sectors across Africa, from where African federations have historically drawn some of their most successful athletes and teams:

For many decades dating back to the pre-independence period, many African countries produced sports talent through the basic education pipeline. Local, national, regional and continental school competitions served as a proving ground for athletes, many of whom eventually went on to represent their countries at international athletic competitions. Eventually, the debt crises of the 1980s, coupled with various domestic political dynamics, saw drastic cuts to public-sector spending, severely affecting education and sports infrastructure.

Many athletic facilities crumbled over time due to lack of repair and upgrades, while funding for physical education programs shrunk and talent cultivation programs suffered as a result. It was also during this period that several contemporary trends became popular, like the building of costly, unsustainable sports infrastructure projects, or white elephants; the uneven allocation of funding to football and other popular sports at the expense of a more balanced set of priorities; and the defection of African athletes to athletic federations in other countries, typically Western but now increasingly Middle Eastern as well.

There is little else I must add to what I wrote three years ago, other than to reiterate that African sports federations must not view their diasporas as an easy way out of the hard work of adequately funding and administering sports locally. Foreign-born athletes are a complement to domestic talent management, and not a replacement for it.

When will the Olympics come to Africa?

Some Africans have long contemplated when the continent would host the summer Olympics. African nations have participated in the games dating back to the colonial era and despite the continent’s strong sporting legacy and enthusiasm for the Olympics, it has yet to host the games. Given Africa’s level of economic development, many on the continent have doubts about whether an African country has the capability to host such a grand event.

Although South Africa won plaudits for its impressive staging of the 2010 World Cup and Morocco is expected to co-host the 2030 tournament with Spain and Portugal, the World Cup did not come without a heavy cost to South Africans and it is debatable whether any benefits accrued from hosting it were tangible enough to justify the large financial outlay and human rights violations.

Some others argue that African countries regularly host international tournaments and noted that concerns about crime in South Africa or the quality of its physical infrastructure proved to be unfounded. Moreover, they say, European and North American cities have hosted the Olympics and other international sports tournaments in less-than-stellar conditions but that has not prevented them from hosting many other international sports events. Thus, these critics argue, African cities only need to be “good enough” and not held to standards that even their wealthier Western peers often fail to meet.

As someone who generally believes that African countries must be laser-focused on poverty reduction, industrialization and building state capacity, and stay clear of expensive frivolities which distract from that mission, I am nonetheless sympathetic to the argument that African countries — some of them anyway — are more capable of hosting global events like the Olympics than the cynicism might suggest. However, the Olympics are of a larger magnitude than the All-Africa Games, AFCON or even the World Cup, whose cost is set to balloon when the pool of participants is expanded from 32 nations to 48.

Most African countries do not have an adequate level of sport infrastructure needed to host the Olympics and must spend already-scarce financial resources to upgrade it, as well as build the residential facilities needed to host more than ten thousand delegates and beef up security and logistics for the two weeks of the games. That realistically means that they will need to borrow more money from foreign sources, which would further plunge them into debt.

The question is not so much whether African countries *can* host the Olympics — they likely could with the right amount of preparation — but if they should. As attractive as the notion might seem and with respect to the argument that Africa is a stakeholder in the games, the Olympics are not and should not be a priority for the continent at this time given the steep costs involved.

That’s my take on the 2024 Olympics. I hope you enjoyed the games as much as I did. For now, I am locked in to the 2024/25 European football season, which started this week. My beloved Arsenal won its first game of the new English Premier League season, which I hope will conclude with the team’s first league championship in 21 years. Watch this space!