How has Faye fared in his first year as Senegal's president?

Taking stock of the tenure of Africa's youngest elected head of state

Earlier this month, Senegal marked two important milestones in its history. On April 2, President Bassirou Diomaye Faye reached the one-year mark of his administration. Days later, he led a national commemoration of the 65th anniversary of Senegal’s independence which included a ceremony that was attended by regional leaders and dignitaries like the heads of state of Gambia, Guinea-Bissau and Mauritania as well as Nigerian Vice President Kashim Shettima.

The convergence of the two occasions made for a suitable opportunity to reflect on the past twelve months in Senegal after the dramatic events of 2024, and take stock of the new administration.

Senegal’s “breakaway” government

Diomaye — as he is mononymously referred to by Senegalese — was keen to demonstrate that he was ready to hit the ground running. On the same day he took the oath of office, he announced the first major decision of his presidency: the selection of Ousmane Sonko, his mentor and closest politically ally, as Senegal’s prime minister. Three days later, Sonko unveiled a list of 25 ministers who would make up what he called a “breakaway” government.

To head the foreign affairs and defense ministries, Sonko selected Yassine Fall and retired Gen. Birame Diop respectively, two professionals with significant experience within the United Nations system. Sonko turned to another retired general, Jean Baptiste Tine, to be Senegal’s minister of interior and public security.

Abdourahmane Sarr, an alumnus of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was picked to be the economy minister while Sonko’s choice for minister of finance was Cheikh Diba, a Sorbonne-trained tax inspector who served in the finance ministry during the administration of former President Macky Sall. Birame Souleye Diop, a former legislator and close Sonko ally, was selected to head the energy ministry, which has taken on strategic significance in light of Senegal’s new status as an oil producer.

The Cabinet generally won public approval — or at least it did not provoke strong objection — although some observers criticized Sonko for selecting only four women as ministers. I was impressed by the swiftness with which the new government rolled out its top appointees and got down to business.

At the risk of seeming to applaud fish for swimming, presidents in many other African countries — looking at you, Nigeria and Kenya! — waste precious time on what is a perfunctory process, and their supporters come up with all kinds of pathetic excuses to justify their dithering. In that regard, Senegal was a welcome deviation from an unfortunate trend.

Diomaye-Sonko’s domestic policy is ambitious

Diomaye came to office with a resounding mandate to lower Senegal's unemployment rate and the high cost of living, fight corruption, implement institutional reforms and enhance the country’s national sovereignty.

When he took office, the unemployment rate stood at more than 20 percent according to Senegal’s statistics agency. Inflation, rising poverty and debt were some of the biggest challenges facing the new administration.

In its earliest weeks, the Diomaye-Sonko administration implemented measures to stabilize consumer prices including subsidies and tax holidays on certain goods like petroleum and electricity. It has set up a commission to review oil and gas contracts Senegal signed with foreign operators, in line with a pledge Diomaye made on the campaign trail.

In October 2024, the government launched Senegal 2050, an ambitious 25-year development plan that seeks to reduce poverty, triple the country’s per capita income by 2050 and ensure annual growth rates of more than six percent from 2025 to 2029. The program would develop new and existing economic industries based around eight interconnected regional hubs across the country.

With Senegal 2050, the new administration aims to boost Senegal’s human capital and accelerate industrialization with the goal of reducing what Sonko called “the vicious cycle of dependence and underdevelopment.” Among its key pledges were one to create training programs for 700,000 youths within the next five years.

In late December, Sonko rolled out his first General Policy Statement as prime minister in an address to the National Assembly. This statement, a stipulation of Senegal’s constitution, sets out the government’s strategic priorities and proposes its policy preferences to the legislature.

Sonko’s policy statement was anchored on Senegal 2050 and underscored its commitment to the goals set out in the initiative. Days after Sonko’s address, the National Assembly approved the government’s 2025 budget of approximately $10.2 billion.

In February 2025, Senegal’s Court of Auditors released a long-awaited review of the country’s finances which indicated that the Sall administration misreported key economic data including debt figures. The audit, which covered the period from March 2019 to March 2024, also showed that the budget deficit averaged more than 10% of gross domestic product from 2019 to 2023, almost twice the 5.5% figured reported under Sall.

In addition, the review found that Senegal’s public debt stood at more than 99% of gross domestic product, well above the previously recorded figure of 74.4%. Last year, the IMF suspended a 3-year, $1.8 billion credit facility it approved for Senegal in 2023 pending the Court of Auditors’ review, and said that the new administration must implement financial reforms in order to access a new credit program.

Senegal’s justice minister announced that he would authorize investigations into facts unearthed by the report. Meanwhile, the government announced austerity measures in response to the harsher-than-expected fiscal constraints revealed by the audit, like the shuttering of some state agencies and the termination of electricity subsidies that it said benefitted the wealthiest people in Senegal. In a televised interview, the minister of the secretary-general of the government hinted at pay freezes for civil servants and tax increases to shore up Senegal's dwindling coffers.

The proposals drew a negative reaction from a public already weary from years of anemic economic performance and cuts to social services, and the administration will face significant pressure going forward to strike a balance between the public’s expectations and the reality of its fiscal constrictions.

Institutional reform, responsibility and “gatsa-gatsa”

Diomaye campaigned against the heavy-handedness and authoritarianism of Sall, whose administration detained him and Sonko until the final 10 days of the campaign for the 2024 presidential election.

In March 2025, a study by the Senegalese collective CartograFreeSenegal counted at least 65 deaths during the popular demonstrations that gripped Senegal from 2021 to 2024. The group echoed widespread calls for accountability and justice for the victims of the violence witnessed during the period.

Sonko said that his government would propose legislation to repeal a controversial law Sall signed that granted amnesty for offenses committed by security forces and protesters during the demonstrations, and which facilitated the release of Sonko and Diomaye before the 2024 presidential election. Earlier this month, the National Assembly approved revisions of that law that removed amnesty for specific crimes including murder, torture and forced disappearance.

The Diomaye-Sonko administration has pursued other reforms, like an unsuccessful effort to dissolve the Economic, Social and Environmental Council and the High Council of Territorial Communities and merge the two organizations into one. Those failed constitutional amendments caused Diomaye to dismiss the heads of the two bodies, dissolve the legislature and call for snap parliamentary elections. PASTEF, Diomaye’s political party, won a supermajority in that poll.

The administration has pledged to push for more reforms including a restructuring of the constitutional council and the judiciary. In May 2024, it launched an online platform, Jubbanti, as part of a national dialogue on judicial reforms that it said enabled citizens to share their views on the best ways to establish a transparent justice system.

The opposition has characterized this drive for reforms and investigations of the previous government as a fig leaf for what it says is the Sonko-Diomaye administration’s desire for retribution. Predictably, the government refutes that characterization and insists that it seeks accountability — or “responsibility,” as its officials have termed it — for actions that it says warrant a reckoning.

To be clear, many PASTEF supporters do want the administration to go after Sall and the officials in his government for alleged offenses committed during their time in office. During his years as an opposition figure, the Wolof phrase gatsa-gatsa, which roughly translates to “an eye for an eye,” came to be identified with Sonko, PASTEF and its supporters as an indication of what their detractors saw as a desire for violence. Many of those critics now believe that the administration has adopted gatsa-gatsa as a governing mantra.

Foreign affairs is one of Diomaye’s calling cards

As a presidential candidate, Diomaye linked domestic issues with foreign affairs by emphasizing themes of national sovereignty that have found resonance across the West Africa region in recent years.

Since taking office, Diomaye has taken a proactive role in Senegal’s foreign relations and made it a major part of his presidency. He has prioritized the improvement of Senegal’s relations with its regional neighbors as a call to order. Several West African heads of state and dignitaries were present at Diomaye’s inauguration ceremony, including the presidents of Nigeria, Ghana and Gambia.

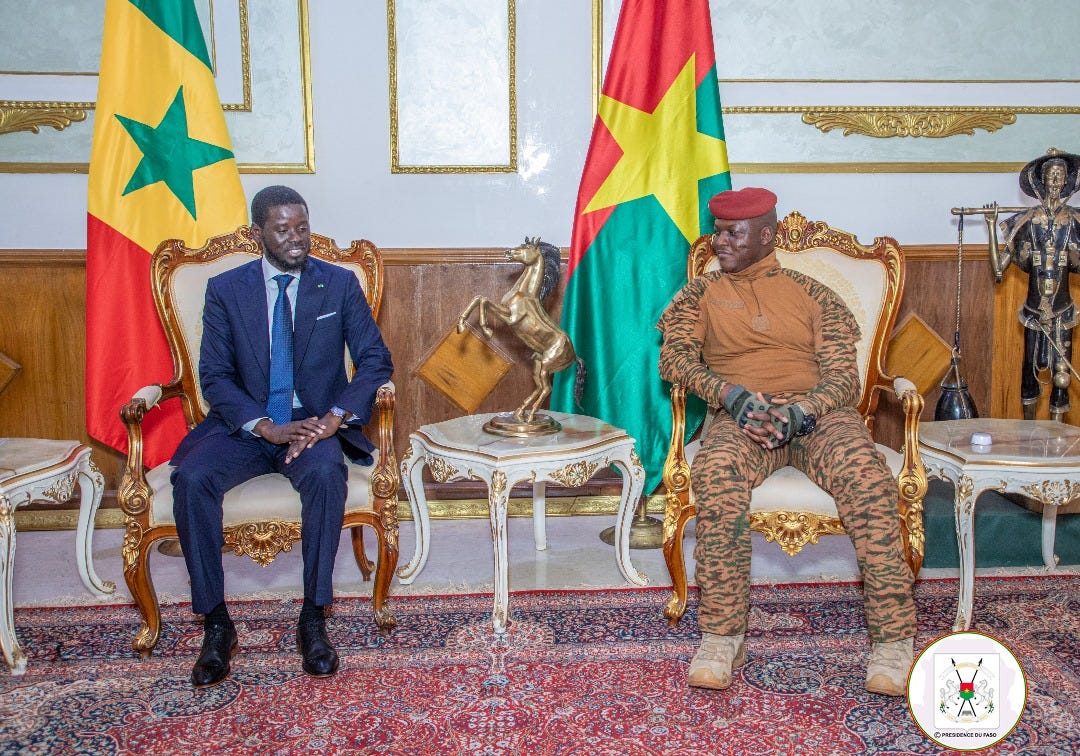

Diomaye made his first official trip abroad as Senegal’s head of state to neighboring Mauritania, and has made stops in Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Côte d'Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Nigeria and Sierra Leone during the first year of his presidency.

In February, Sonko signed a peace agreement in Guinea-Bissau with a faction of the Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance, a separatist movement in Senegal’s Casamance region. Implemented under the mediation of Guinea-Bissau’s President Umaro Sissoco Embalo, this initiative is part of the Diomaye Plan for Casamance, the Senegalese government’s roadmap for promoting peace and development in the region.

As the head of state of the only West African nation to have never experienced a military coup, Diomaye has generally upheld Senegal’s role as a norm entrepreneur on issues of democratic governance in the region. At a summit in July 2024 of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), he was appointed alongside his Togolese counterpart Faure Gnassingbé as a mediator between the regional bloc and the Alliance of Sahel States, a confederation consisting of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger which formally broke away from ECOWAS in January 2025.

To bolster his position as a regional mediator, Diomaye appointed Abdoulaye Bathily, a respected Senegalese scholar and diplomat, as his special envoy to the AES. Diomaye’s mediation did not prevent the three Sahelian states from severing ties with ECOWAS but his ability to bridge the divide between the two sides could help to preserve cordial relations that could prove useful down the line.

Regarding Senegal’s relationship with France, its former colonial power, Diomaye has reiterated his desire to restructure bilateral ties towards what he called a mutually beneficial partnership. In the runup to the 80th anniversary of the Thiaroye massacre, in which hundreds of black African soldiers who fought for France during World War II were gunned down by French colonial forces after they protested against their unpaid wages and poor conditions at the Thiaroye military camp, Diomaye exchanged letters with French President Emmanuel Macron which included a first-ever acknowledgement by Paris that the shooting constituded a “massacre.”

In his response, Diomaye called for France to commit to a transparent, frank process toward “the whole truth about this painful event.” In an interview with AFP, he called for France to close its military bases in Senegal. Weeks later, Sonko announced during his general policy statement that the government would close “all foreign military bases.” The French government said last month that it had handed back control of two military facilities to Senegal. (More on Africa’s evolving relations with France in a future post.)

As with domestic issues, Diomaye has had to perform a highwire act in trying to reconcile different interests on foreign affairs. Even while calling for a “rupture” in Senegal’s neocolonial relationship with France, Diomaye maintained that Senegal did not seek a total break with France, saying that the country remained an important economic partner and his administration sought cordial relations with Paris just as it would with any other foreign interlocutor.

Recognizing Senegal's limited international leverage, the Diomaye-Sonko administration has sought to be on good terms with the European Union and United States as well as the IMF, World Bank and other international institutions dominated by Washington and its European allies. It has taken few tangible steps toward withdrawing from the CFA franc, an issue Sonko made a central plank of his agenda while in the opposition.

By the same token, Diomaye and Sonko can read maps and know who their neighbors are. Senegal shares a land border with four countries including Mali, many of whose nationals live in Senegal. In other words, Senegal is an interested party to political and security developments in the Sahel, and must maintain dialogue with neighboring states.

In addition, many of the Diomaye-Sonko administration’s supporters approve of the military rulers in Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger and the sovereigntist positions around which these officers have built their legitimacy. It is common to see images of the junta leaders on walls and buildings in Senegalese villages, towns and cities. Guinea’s military ruler, Gen. Mamady Doumbouya, received the loudest cheers from attendants when foreign dignitaries were introduced into the venue of Diomaye’s inauguration ceremony.

As a head of state, Diomaye has navigated these minefields reasonably well but time will tell how far Diomaye’s diplomatic skills can go amid the reordering of regional and global orders that is taking place.

Diomaye Mooy Sonko?

During the presidential campaign, Diomaye Mooy Sonko — meaning “Diomaye is Sonko” in Wolof — was a popular refrain among PASTEF’s supporters, and the slogan made its way onto posters, billboards, t-shirts, stickers and an infectious song that doubled as an unofficial campaign anthem. The phrase gained currency after Diomaye was selected as PASTEF’s flagbearer for the 2024 presidential race.

Since the new administration took office, some observers have raised questions about the ability of Diomaye and Sonko to coexist as governing partners. Speculation about possible tension between them refuses to dissipate, despite their deep personal bond and public exhortations that they are politically inseparable. Some have even talked up the possibility of a power struggle akin to the rift between former President Leopold Senghor and Mamadou Dia, Senghor’s one-time ally and prime minister who he later accused of plotting a coup against him and dismissed from office. Dia was later convicted of treason and sentenced to prison, but was later pardoned by Senghor.

The speculation is not entirely irrational, given that Sonko’s presidential ambition was no secret. He did not run in the 2024 presidential election only because he was disqualified from the race due to a conviction for defamation, which enabled Diomaye to run as PASTEF’s nominee in his stead. It is sensible to wonder how the two men will manage the power-sharing burden over the long haul given that Sonko technically remains the party’s leader, but one can take them at their word that they can manage the dynamics of their relationship even amid any tensions that might rise as part and parcel of any governing administration.

Outlook

All things considered, the Diomaye-Sonko administration has had a decent start to its tenure. Whatever one thinks of its ideas — I am supportive of its stated goals — the government cannot be accused of lacking a vision or desire to get things done.

That much of its policy output has been disappointingly conformist and neoliberal in several respects is down to several factors including the government's lack of a legislative majority during the first five months of its administration and a global political economy that curbs the enthusiasm of ambitious peripheral states which seek even the slightest deviation from the Western-led global capitalist hegemony.

Most significantly, Diomaye and Sonko are not as revolutionary as many including their supporters and critics alike might have believed. It is common to see the two men — as well as the Sahelian junta leaders — described in international press with terms like “radical” or “left-wing Pan-Africanist.” At best, those terms are approximations of the worldview of Diomaye and Sonko using Western political shorthands that have little applicability in African contexts.

In reality, Diomaye and Sonko are traditionalists who hold diverse, broadly conservative views on a range of domestic and international issues that reflect common perspectives in Senegal and the West Africa region. Despite the “radical” tag that is commonly applied to them, they have proven to be pragmatic administrators and their appointments were generally conventional choices that could easily have been made by Amadou Ba — Sonko’s predecessor and Diomaye’s closest challenger in last year’s presidential race — or any previous government.

The Diomaye-Sonko administration remains generally popular with the Senegalese public, as evidenced by the supermajority PASTEF won in November’s parliamentary vote. If a presidential vote were held today with Diomaye on the ballot, he would likely win again.

At the same time, the population is increasingly becoming agitated by what it believes is the government’s slow pace and insufficient achievements to date. Threats by unions to go on strike over the administration’s austerity measures and protests by motorcycle riders popularly known as “jakartamen” in response to the government’s demand for mandatory registration of motorcycles are two indications that the public will not remain patient indefinitely.

For the remainder of its term, the administration must religiously implement its Vision Senegal 2050 development plan while reducing unemployment and inflation in the short term. It must take serious steps to strengthen institutional guardrails that previous administrations have weakened over time.

Equally, it must pay attention to Senegal’s environmental challenges, including water scarcity and the climate change-driven rising sea levels that are causing an increase of coastal erosion in Senegal and negatively affecting agriculture, fisheries and the tourism sector. The administration will likely not be able to prevent every single one of its youths who seeks greener pastures overseas from leaving, but it must work to minimize the deaths and entrapment of its nationals in dangerous conditions abroad.

Senegal is one of the African countries which lost all its U.S. foreign assistance funds because of the Trump aid cuts, and the administration will struggle to seamlessly replace those funds and adjust quickly to a “post-aid” world. Small, low-income countries like Senegal will not find it easy to navigate a rapidly evolving global order that is increasingly characterized by a rejection of multilateral cooperation by its major poles, and that is why Dakar cannot afford to be provincial in its worldview. Senegal’s cosmopolitanism, openness and history of support for African integration and multilateralism bode well for its ability to form crucial global partnerships needed to shore up its international position.

The Diomaye-Sonko administration has a lot of ambition and faces heightened expectation, but it does not have the financial resources and geopolitical heft needed to achieve all of its objectives. It must find a way to reconcile ways, means and ends if it intends to retain the support of the citizens whose lives it promised to transform.