Nigeria's #EndBadGovernance protest was the first big wake-up call of Tinubu's presidency

Directionless "reforms," repression and wheel-and-deal games will not help Tinubu fix Nigeria's societal challenges.

#EndBadGovernance: Nigeria’s August of Fury

For ten consecutive days beginning August 1, Nigerians took to the streets to protest the rising cost of living, growing economic hardship and the dismal state of governance in the country. The demonstrations were organized by a loose array of civic groups under the popular hashtag #EndBadGovernance and were centered around — but not limited to — large cities and state capitals like Lagos, Ibadan, Kano, Port Harcourt, Maiduguri and Abuja.

The protests were not triggered by a specific incident but are better seen as the latest eruption of popular anger over worsening societal conditions and government malfeasance in the roughly 15 months since President Bola Tinubu was sworn in to office. He and other political elites failed to detect the barely concealed discontent and restlessness among a public forced to endure increasing levels of hunger; persistent insecurity; recurrent interruptions to basic services like electricity, telecommunication and banking; and scarcities of food, fuel and even cash.

In office, Tinubu has regularly called for Nigerians to make sacrifices amid the present difficulties for the promise of a better future, but he and the rest of Nigeria’s political class have failed to meet the public halfway. At a time when starvation and destitution are widespread across Nigeria, federal and state budgets continue to be overloaded with wasteful nonsense of little developmental value.

The Tinubu administration has spent ungodly sums of money on items that include a presidential jet, limousine and a yacht; subsidies for Muslim pilgrims traveling to Mecca; new cars for Nigeria's first lady and members of the National Assembly; and upgrading Vice President Kashim Shettima’s residence at the cost of the equivalent of $13 million.

Thus, it should not have surprised Tinubu that Nigerians would lose their patience with his administration’s inability to improve their livelihoods. But his reaction to the demonstrations has been true to form. Having regularly dismissed suggestions that his policies were adversely affecting Nigerians, Tinubu responded to the demonstrations with a mixture of inveigling and repression.

When activists rebuffed government offers of “negotiation,” the state swiftly turned to tyranny. No fewer than 22 people died during the demonstrations, hundreds more were injured and thousands of individuals including protesters were arrested, with many later charged with a range of offenses. Although the demonstrations came to an anticlimactic end on its final day, activists have vowed to organize more protests in October.

Tinubu probably believes that he will be able to ride out any future demonstrations just as he looks to have done now, but the anxieties that caused Nigerians to take to the streets earlier this month are unlikely to disappear any time soon. Repression will not resolve Nigeria’s economic challenges and Tinubu would be wise to listen to his constituents and engage them in meaningful dialogue aimed at solving problems.

Tinubu is giving Nigerians the best that he’s got … and it’s not good enough

As a presidential candidate, Tinubu ran a dull, low-energy campaign that lacked a compelling vision for Nigeria much less any details about how he would govern the country.

To the extent that Tinubu spoke at any length about policy, he pledged to eliminate Nigeria’s petroleum subsidies, simplify the country’s multiple exchange rates into one and invigorate the oil sector by deregulating prices and increasing production. More broadly, he touted his experience as a business executive and a former governor of Lagos — Nigeria’s wealthiest state and economic capital — as assets that gave him the inside track to implement what he said were tough but necessary reforms needed to resuscitate Nigeria’s moribund economy.

Upon taking office, Tinubu signaled to observers that he meant business. During his inauguration address, he famously declared that “fuel subsidy is gone.” Weeks later, he directed Nigeria’s central bank to implement a unification of exchange rates. International financial institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund cheered both moves, while a coterie of observers that included foreign investors and prominent Western media outlets like The Economist, Financial Times, Bloomberg and the Wall Street Journal praised them using glowing terms like “bold reforms.”

The elimination of the petroleum subsidy and the devaluation of the Nigerian naira in quick succession turbocharged inflation to a level not seen in two decades. The price of petroleum quadrupled, as did the cost of other essential goods and services like food and transportation. The value of the naira against the U.S. dollar fell to record lows, and it has been among the worst-performing currencies in the world since Tinubu took office.

Earlier this year, the Nigerian government introduced drastic hikes to the price of electricity that increased by as much as 300% for some customers, but power supply remains abysmal. The frequent cuts and national blackouts Nigerians have been accustomed to for decades continue to this day, while Nigeria’s electricity generation capacity has dropped this year. Nigeria’s power minister has suggested that further price increases could be in the offing.

Tinubu's calamitious 15 months in office should not come as a surprise. The raison d'être for his presidential campaign was “emi l’okan,” a Yorùbá phrase which roughly translates in English language to “it is my turn” or “I am next.” On the specifics of economic policy, he demonstrated a fallacious tendency common among African government officials which considers “reforms” designed to win the approval of Western governments, international organizations and other foreign donors as ends in themselves and not a means to specific outcomes.

The claim by Tinubu and his supporters that he was the architect of a so-called Lagos model of governance — a myth that many foreign observers with impressive-sounding credentials have legitimized — was an exaggeration. If a “Lagos model” exists, it is a neoliberal statist mix of aggressive taxation; a lack of transparency in public finance; a deteriorating physical infrastructure; the displacement of vulnerable populations; and the construction of malls, plazas and shopping complexes as symbols of prosperity. When weighed against the standards set by Brigadier Mobolaji Johnson and Lateef Jakande, Lagos’ most transformative governors, Tinubu’s tenure falls considerably short in comparison.

Tinubu’s presidential cabinet was an uninspired collection of poorly-performing former governors and other loyalists with few discernible talents and a thin record of achievement. His style of governance is heavy on photo-ops and public announcements and light on careful deliberation, as I noted around the 100-day mark of his presidency. Alas, Tinubu cannot not give Nigerians what he does not have.

Clearing up misconceptions about #EndBadGovernance

A few corrections to some common claims about the August 2024 protests are in order.

First, it would be wrong to say that Tinubu and the rest of Nigeria’s political class were caught off-guard by the #EndBadGovernance protests, not least because they were not quite as spontaneous as some commentators claimed. Indeed, some of the organizers gave public notice for several weeks about their plans to hold demonstrations. Their announcements gave way to a carrot-and-stick effort by the political class to dissuade the protests. Powerful actors including federal ministers and state governors — mainly but not exclusively from the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) — enlisted key segments like traditional rulers, unions, student groups, social media influencers and religious leaders as part of that effort.

Days before the protests commenced, Tinubu met with a group of influential Muslim clerics in order to stave off demonstrations in Northern Nigeria, where some claim Tinubu’s popularity has waned since he took office. Equally, the Nigerian Army threatened to crack down on the protests if they descended into what it described as “anarchy.” These interventions were not successful at deterring the protests but they likely had some effect in causing some groups to back out of them.

The popular assertion by many including some Nigerians like the inspector-general of police and even supporters of the #EndBadGovernance protests that they were “inspired” or “triggered” by Kenya’s protests is preposterous. As I remarked to Al Jazeera, protests over the cost of living have been frequent since Tinubu’s inauguration. Nationwide strikes by unions and demonstrations against soaring inflation and living costs have been a recurring pattern since Tinubu took office in May 2023, with the first wave having commenced less than three months into his presidency. They have continued unabated virtually every step of the way. On June 12, Nigerians in several states marked the Democracy Day holiday with protests demanding an end to economic hardship and insecurity.

As noted by two Nigerian political scientists, the August 2024 protests are part of a trajectory of public demonstrations that date back to 2012’s #OccupyNigeria uprising and include 2020’s #EndSARS protests. Invariably, news developments almost always have local origins and need very little external spark. This does not suggest that participants do not learn from other contexts or that some external influences don't exist, but it means that in trying to make sense of global events — particularly in undercovered, poorly understood parts of the world like Africa — it is best to analyze issues and events on their own terms and not to conflate contexts that might not have much in common beyond headlines.

Some of the international outlets that cheered Tinubu’s “bold reforms” appear to be blowing with the wind amid backlash to his policies. They and others seem to be rethinking the implementation — if not quite the notion — of these measures and have increasingly described them as “shock therapy.” Tinubu’s policies can be described in many words but “shock therapy” would not be among them, except perhaps if the term means something other than what it has traditionally described. Describing Tinubu’s policies as “shock therapy” would be projecting coherence and strategic thought onto an administration that takes a scattergun approach to governance and lurches from one crisis to another without the slightest hint of lucidity.

The “bold reforms” Tinubu was praised for have been more hype than reality. The supposed “free float” of the currency did not happen, and Nigeria’s central bank admitted last year that it implemented a managed float of the naira that differed little from the status quo ante. More broadly, the opacity in Nigeria’s foreign exchange market as well as its capture by a range of vested interests that includes political elites, banks and other large corporations still exists.

As Nigerians widely suspected, the Tinubu administration covertly reinserted the petroleum subsidies to stabilize the price of oil and other commodities, even as it continues to insist that “fuel subsidy is gone.” Tinubu is spending more money than his predecessors, at least in nominal budgetary terms, and his administration has handed out the equivalent of hundreds of millions of dollars in emergency relief to farmers as well as cash transfers to poor households, among other major expenditures.

To be clear, I applaud Tinubu’s public spending and it is to his credit that he reversed course on some of the imprudent policies that he should have never implemented to begin with. Contra some commentators, Nigeria’s problem is not that its governments spend too much money but that they spend too little of it for a country of its size and the funds that they do spend are poorly allocated in deeply unproductive ways. Whatever one thinks of Tinubu’s policies, they do not resemble those of Argentina’s Javier Milei, an avowed shock therapist who wholeheartedly embraces the label. Tinubu’s economic policies have 99 problems, but “shock therapy” ain’t one.

Tinubu is a powerful president handicapped by weak legitimacy

Tinubu was sworn into office with a weak mandate and under a cloud of legitimacy. His biography has long been shrouded in mystery and controversy over basic details like his age, educational credentials and professional background. Believed to be one of Nigeria’s richest politicians, the source of his personal wealth has always attracted scrutiny. As the undisputed political heavyweight in South West Nigeria and specifically Lagos, where he served as governor from 1999 to 2007, Tinubu has been unable to shake longstanding allegations of corruption, which he has always denied.

In last year’s presidential election, only 27% of eligible voters cast a ballot, the lowest figure recorded since 1979. The approximately 37% of the vote Tinubu garnered was the smallest share of any winning candidate since Nigeria’s return to civilian rule in 1999. Tinubu’s victory came down to the quirks of a majoritarian first-past-the-post electoral system that often makes triumphant candidates seem more popular than they are. He was the beneficiary of what essentially amounted to a split in the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), Nigeria’s largest opposition party.

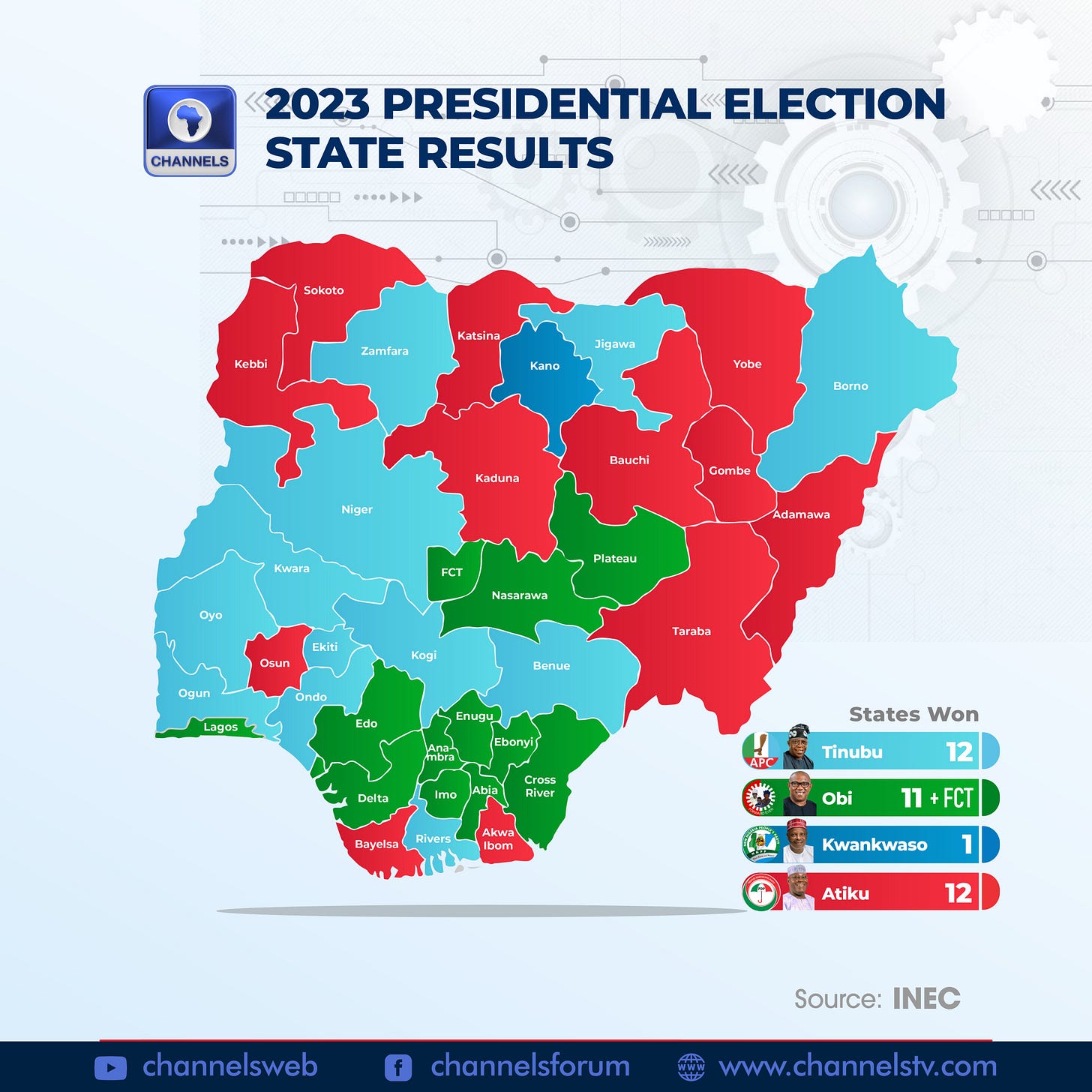

Tinubu’s three closest challengers in the 2023 poll, Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso, Peter Obi and former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, were all members of the PDP a year before the vote. Kwankwaso and Obi left the party before it held its presidential primary in May 2022, and won their bids to represent other parties in the 2023 election. As the winner of the PDP presidential primary, Abubakar was the party's flagbearer for the vote. In the final tally of the election, Obi and Abubakar received 25% and 29% of the vote respectively, while Kwankwaso pulled 6%.

The 2023 presidential election was a shambolic exercise that featured credible instances of malpractice, voter suppression, violence, excessively long delays and malfunctioning technology, all of which transpired despite Nigeria’s electoral commission having received the equivalent of approximately $223 million from the National Assembly to prepare for the general election. Abubakar and Obi challenged the result of the presidential vote, but their efforts were unsuccessful and Tinubu’s victory was upheld by the courts.

But if the manner and slenderness of Tinubu’s victory, or the sullen mood across the country on the eve of his inauguration after eight dreadful years under his predecessor Muhammadu Buhari implied a lack of enthusiasm for only Nigeria’s third peaceful transfer of power between elected civilian leaders since independence, Tinubu did not seem to mind. He took office with a swagger and an air of invulnerability that underscored his 25-year sojourn from exile in the United Kingdom during the gloomy years of Gen. Sani Abacha’s regime to the presidency of Africa’s most populous nation.

Tinubu’s party retained its majority in the National Assembly and his handpicked choices to lead its two chambers were confirmed with ease. APC governors also maintained control of 20 of Nigeria’s 36 states. For the first time since Nigeria’s independence from British colonial rule, Lagos is completely in tandem with Nigeria’s federal government. More broadly, Tinubu is continuing apace with his effort to complete what would be an unprecedented achievement in Nigerian political economy: A full alignment of Abuja — Nigeria's capital — with Lagos, Kano, Rivers and Borno states.

All four states are large, vote-rich electoral prizes (Lagos and Rivers are also Nigeria's two wealthiest states) and pushing them to closer cooperation with the federal government would put Tinubu in pole position to win reelection in 2027. If Tinubu took office with a weak mandate, his consolidation of power at a level unseen since 1999 has been anything but discreet.

Unfortunately for Nigerians, Tinubu has proven unable to put his immense political capital to tangible use as demonstrated by the disjointedness of his so-called bold reforms. In a sense, that is by design. Nigeria’s paradox is that the power of the executive branch continues to increase relative to the other two arms of government but the Nigerian state writ large has never been weaker and more bereft of capacity needed to fulfill its basic functions.

In addition, Tinubu squeaked out a win in an incredibly close presidential contest by undercutting traditional powerbrokers — particularly in Northern Nigeria — and creating new electoral mainstays across the country. This necessarily constrained his choice of personnel to fill key positions in his administration, and his Cabinet was stocked with cronies whose record of effective public service and visionary leadership is weak. In the National Assembly, the APC caucus and its parliamentary leaders appear to believe that they are accountable not to their constituents but to Tinubu.

Nigeria’s governors face a bigger crisis of capacity and legitimacy in their states and most are too incompetent to oversee something as basic as ensuring that civil servants are paid their salaries every month. The PDP, which remains beset by years of infighting that arguably cost it a winnable presidential race last year, lacks any interest in putting up meaningful opposition to the APC. In any case, Tinubu has considerably neutered the party by coopting several of its heavyweights including a former governor of Rivers who Tinubu appointed to run the Federal Capital Territory.

In a nutshell, the preeminence Tinubu enjoys as president is in tension with structural realities about Nigeria’s political economy that make it incredibly difficult to govern the country effectively.

Can Tinubu turn things around?

With less than 18 months of his four-year term in the rearview mirror, Tinubu has enough time to right-size his government but the clock is ticking. Having been starved of goodwill from the onset of his administration on account of the nature of his electoral victory, he chose to focus on consolidating power at home and impressing foreign interlocutors.

Tinubu did not invest enough time in setting a governing agenda or filling out his administration with competent individuals. He took far too long — about two months — to roll out a Cabinet that underwhelmed when it was announced. Most of Tinubu’s ministers have floundered but he has not deemed it fit to make significant replacements. There is still enough time to make important personnel changes that reflect the urgency of the moment.

Tinubu must finally articulate a vision that would underpin the remainder of his term and connect it to a set of tangible, interconnected objectives. Piecemeal “reforms” which win the adulation of international financial institutions and the pages of The Economist but are poorly anchored to conditions on the ground or lack correlation with any decipherable goals will neither attract the foreign investment Tinubu desires nor improve the livelihood of Nigerians. The best way for Tinubu to keep protesters off the streets is not through repression, but via dialogue and a course correction that treats the Nigerian public as his principal constituency.

Great article