Nigeria's insecurity is rooted in its colonial security architecture

The country's security crisis symptomizes a weak state whose decrepitude has reached breaking point.

Several high-profile incidents this year have brought Nigeria's kidnapping menace into sharp focus.

In January, residents of Abuja —Nigeria’s capital — were rocked by reports of a spate of abductions in the Federal Capital Territory including that of a seven-member family. In February, jihadist rebels abducted at least 200 internally displaced people in the northeastern state of Borno state.

Earlier this month, Nigeria made international news when more than 280 students were kidnapped from their school in the northern state of Kaduna. That incident overshadowed another abduction that reportedly took place a few days later, when no fewer than 61 people were kidnapped by armed bandits in a nearby part of Kaduna.

This past weekend, gunmen were said to have kidnapped up to 100 people in two fresh attacks in Kaduna. It is entirely possible that there were flash points across the country that have been forgotten or did not make headlines at all.

Kidnapping is hardly the only dimension of Nigeria’s security crisis

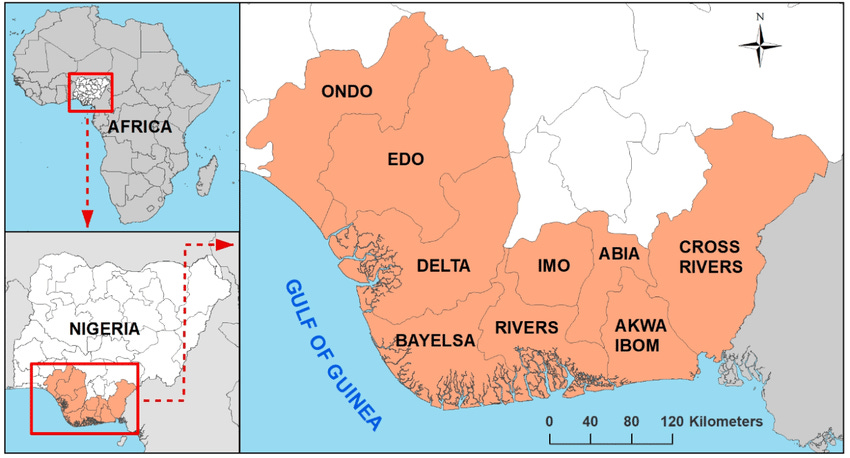

The news that 16 Nigerian soldiers were killed last week in Delta state hit different, as the kids say. It was also a grim reminder of the many dimensions of violent insecurity that abound across the country.

A Nigerian Army spokesperson said that the soldiers, who were deployed to the state on a “peacekeeping mission,” were killed on March 14 after they responded to a distress call triggered by a communal clash between the Okuoma and Okoloba communities. The full circumstances of their reported killings are still unclear, but triggered immediate outrage among the political class.

In a statement, President Bola Tinubu condemned the “wicked act” and instructed the nation’s military authorities to “bring to justice anybody found to have been responsible for this unconscionable crime against the Nigerian people.” The governor of Delta state, Sheriff Oborevwori, echoed Tinubu’s statements and visited the community where the killing reportedly took place. The Nigerian Senate has also tasked one of its committees with investigating the killing of the 16 soldiers.

No sooner had the news of the soldiers’ killing filtered across Nigerian traditional and social media spaces than many residents of Okuama community fled their homes. And if local reports are to be believed, they were wise to do so as the Nigerian Army has decided to act as judge, jury and executioner in this case.

In recent days, several Nigerian outlets have run stories of alleged reprisal attacks by soldiers against the Okuama community, where locals have reported that tens of people have been killed and houses burned down. The attacks have reportedly extended to neighboring Bayelsa state, suspected to be the hideout of one of the militants alleged to be involved in the killing of the soldiers. Nigeria’s military authorities have denied the reports of reprisal attacks, and dismissed them as “propaganda.”

Nigerian security forces have a grisly track record of violent reprisals

Reprisals by Nigerian soldiers and other security forces against local communities have a lengthy history and date all the way back to the mid-19th century, when British colonizers created the so-called Glover Hausas to secure trade routes around the Lagos colony and launch punitive expeditions against local populations in its hinterlands.

The unit was created to essentially double as a police and military force for British colonial authorities. The Glover Hausas were the forerunner of the Nigerian army and police, and the collective punishment contemporary Nigerian soldiers are known for were a staple of the Glover Hausas, which morphed into several new entities including the Southern Nigeria Regiment before becoming what is known today as the Nigerian Army.

The history of punitive expedition-style reprisals by Nigerian soldiers and other security forces is as lengthy as it is grim. The 1999 Odi massacre, perhaps the most infamous example in recent history, was said to be in response to the killing of 12 police officers and an ambush of soldiers by a militia that reportedly hid among Odi’s civilian population.

The tragedy inspired a song titled “Dem Mama” by the singer Timaya, who hails from Odi. Other notable examples including the 2001 Zaki Biam massacre, the 2008 Ogaminana masscre, the 2015 Zaria massacre and the 2020 Oyigbo massacre.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of the total number of incidents of reprisals by Nigerian security forces, as there are regrettably so many more examples including last year’s attack on a community in the southeastern state of Imo.

Nigeria’s security crisis begins with the weakness of the state

It is worth noting that civilians also died in last week’s communal clash in Delta, underscoring the interplay of communal conflicts and the armed militancy that has gripped the Niger Delta over the past three decades.

The political economy of natural resources and violent conflict in the region is such that powerful anti-state militants leverage their ability to deploy violence to bargain with the state and become part of the ruling class. These militants, who are generally embedded in their communities and even neighboring ones, are unlikely to turn away from violent means of dispute resolution as long as they have the incentive to do so.

Some of those factors appear to be at play in this incident in Delta state, although it remains to be seen to what degree. Longstanding communal conflicts among and between local communities, when combined with a breakdown in security across the community and the weakness of key state institutions like the police and judiciary, inevitably led to a mission creep by Nigeria’s armed forces.

Left unaddressed by most Nigerian political and security elites is perhaps the most important question they should be asking, namely why was the Nigerian Army tasked with "peacekeeping" responsibilities in a domestic conflict to begin with? Of course, to ask the question is to answer it and the potential responses would inevitably raise many more questions and issues that Nigerian political elites find deeply uncomfortable, like the country’s obsolete security framework that can barely secure even the seat of national government.

In recent media rounds I have done, I have often argued that the Nigerian state’s inability to secure lives and property is rooted in structural flaws that cannot be easily revamped by the kind of piecemeal “security sector reforms” international donors and foreign governments are enamored of. As I wrote in a 2022 piece in World Politics Review:

… the thread that connects [incidents of violent insecurity in Nigeria] is an obsolete security architecture that was birthed in the colonial era and hardened by decades of military rule, one that was created for the purpose of repression and regime security, not to secure the lives and property of Nigerians. Its inability to maintain a monopoly on violence or safeguard the territorial integrity of Nigeria, to say nothing of the lives of its citizens, is a feature, not a bug.

Is a demilitarized Nigerian security architecture possible?

In truth, there are no easy solutions to Nigeria’s security difficulties, as the problems are interconnected and not easy to resolve in isolation of other societal challenges, a point that many critics do not appreciate as much as they perhaps should. At the same time, the country’s political elites continue to live in denial about the scale of the security problem and seem content with the status quo despite mounting evidence that it is unsustainable.

For instance, there is widespread acknowledgment that the continued deployment of the army and other military forces across the country to carry out internal security functions is ineffective and worsens the country’s already poor civil-military relations. But few political leaders are willing to take concrete steps toward an alternative that meets contemporary realities and is sustainable, notwithstanding the frequent calls for “state policing” and other forms of subnational law enforcement.

Today, Nigerian soldiers do everything from traffic control and securing polling stations to protecting VIPs and hunting down bandits and jihadists. Many Nigerians—including leaders of the armed forces—recognize that this is a problem, but some equally believe that the military is the only institution capable of securing the country.

This is not an insignificant notion in a country where the army has ruled for nearly half of its post-independence history and major cities including Lagos, Ibadan, Port Harcourt, Calabar, Kaduna, Maiduguri and Abuja are littered with military bases that have existed for decades. Despite decades of the Nigerian military’s documented human rights abuses and a decline in its professionalism, it remains an unmissable part of life in the country and many Nigerians still hold it in high regard, at least in comparison to the police and other institutions. Incidents like last week’s killing of 16 soldiers in Delta—as well as the reaction to it—are a reminder of the perils of the army’s embeddedness in civic life, but that alone is unlikely to change the status quo.

In what is surely a historical plot twist, the Nigerian Army today doubles as a police as well as a military force much like the Glover Hausas before it did.

Thank you for this insightful piece. As you’ve concluded, the Nigerian Army is ever present in civilian affairs, partly due to the ineptitude of the Nigerian police to maintain law and order. What the police lack in tact, the army makes up for in brutality. Ìkan ò gbèkan bí òwu jàngo (loosely translated as “none is better than the other”)

The Nigerian army is a relic of the past and I’m afraid it will remain so. Why? Because the elites and the ruling class enjoy the status quo. There’s something fundamentally wrong with the social contract.