Balance, modernization and a shared vision: FOCAC 2024 and the next phase of Africa-China relations

China is Africa's most important foreign partner. But the relationship needs to be updated to future realities.

24 to 25: FOCAC as a symbol of the growing ties between Africa and China

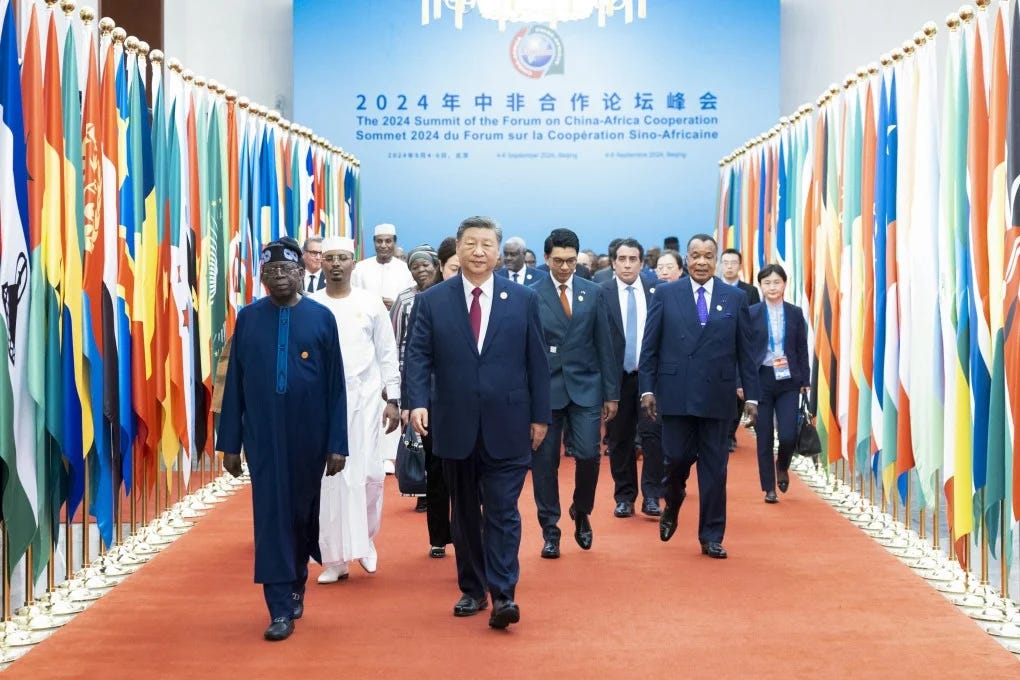

African leaders converged in Beijing last week for the 24th edition of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). More than 50 African heads of state and government attended the gathering, as did top officials from the African Union (AU) and United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

The forum was established in 2000 as the premier mechanism for multilateral engagement between China and the member states of the Organization of African Unity, the AU’s predecessor organization. Since then, the triennial meeting, which typically rotates between China and an African country as the host, has expanded from a ministerial conference to an all-encompassing affair that the two sides pull out all the stops for.

For African governments, the forum sometimes marks the unofficial launch of their diplomatic calendar in the year that it is held. Many more African leaders attend it than the number which travels to New York for the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), and FOCAC usually features the largest gathering of African heads of state and government aside from the annual summit of the AU’s leaders.

The photo op of the Chinese leader and his individual African counterparts has become a treasured ritual that presidents across the continent proudly disseminate at home as evidence of their claim to international legitimacy. African private sector organizations, industry associations and media also attend the forum and pay close attention to its deliberations. Put simply, the importance Africans place on FOCAC cannot be overstated.

FOCAC’s expansion is symbolic of the remarkable growth of the modern relationship between African countries and China, which is the continent’s largest trading partner and a major source of foreign direct investment inflows. Since 2000, China has provided more than $180 billion in loans to African countries and regional organizations, according to Boston University’s Chinese Loans to Africa Database. All but two of the AU’s 55 members have signed on to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Bilateral trade between African countries and China reportedly reached a record $280 billion last year.

As China has grown more assertive in multilateral institutions like the United Nations (UN), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Trade Organization (WTO), Beijing has deepened its diplomatic cooperation with African states — which typically make up more than a quarter of the members of these bodies — and readily aligns itself with them on the major issues that are taken up by those institutions.

China tends to be in sync with the so-called Group of 77 (G-77), a coalition of developing countries in the UN that counts continental giants like Nigeria and Kenya as founding members and many other African states as current members. Though China technically does not consider itself a member of the group, it nonetheless provides it with diplomatic and financial support, and the group’s official statements are formally signed as “The Group of 77 and China.” By any reasonable measure, China is Africa’s most important diplomatic partner by some distance.

Africa was a little nonplussed about FOCAC 2024. Here’s why.

The anticipation that typically accompanies FOCAC was noticeably lacking this year on the African side. The usual buildup to the forum seen across media and other non-government sectors across the continent was diminished. Even among government delegations, which turned up in their usual large numbers, much of the tone struck by African heads of state and other top officials was more circumspect and apprehensive than usual.

Some observers pointed to the smorgasbord of “One-Plus-Africa” summits and the growing criticism they have generated among African publics as a reason for the quieter buildup to this year’s FOCAC but those “Africa summits” existed in previous years when FOCAC found more enthusiasm. It is more likely that recent trends and developments in Africa-China relations, including growing debt concerns, trade imbalances, longstanding tensions over Chinese labor and commercial practices as well as a perception among some Africans that China is pulling back from the continent explain the diminished enthusiasm for FOCAC 2024 seen in many African quarters.

Last year, China approved loans worth more than $4 billion for eight African countries and two regional organizations, marking the first time since 2016 that African countries saw an increase in the annual loan amount they received from China. But that figure was considerably lower than the average of $10 billion in annual commitments disbursed during the peak years of the BRI.

To many African citizens, the drop in lending figures was indicative of its flickering interest in their country. Emergent debt woes, their impact on domestic politics and Chinese reluctance to provide the kind of debt relief sought by countries like Zambia and Angola fuels the suspicion among some Africans that China is shrinking its footprint on the continent.

Chinese officials at FOCAC 2024 were keen to counter the impression that Beijing was reducing its commitment to Africa. During his keynote address to the forum, President Xi Jinping pledged more than $50 billion to African countries over the next three years, including access to credit lines, aid, investments by Chinese firms and assistance for African countries to issue renminbi-denominated “panda bonds.” In addition, he announced that Beijing will create one million jobs across the continent and grant zero-tariff treatment for 100% tariff lines to the 33 African countries which are classified as members of the Least Developed Countries (LDC).

In celebrating the decades-long partnership between China and African nations, Xi referred to a “shared vision” of the future that he said “will set off a wave of modernization in the Global South.” The broader Beijing Action Plan sets out the key measures Chinese officials resolved to take in support of Africa for the next three years, including 10 partnership initiatives in key areas like trade, industrial development, digital connectivity and green development.

These pledges received near-unanimous approval among African government delegations, media and ordinary citizens, and went some way in assuaging concerns that Beijing is downsizing across the continent. As a result of domestic shifts in China — evidenced by a weak post-COVID recovery, a slowdown of growth, a real estate crisis and demographic challenges — and a turbulent global environment beset by great-power competition, external shocks and the uneven performance of Chinese projects overseas, the BRI is transitioning from large, expensive infrastructure projects to a “small and beautiful” approach that leans toward greener, less risky ones. That shift has caused considerable nervousness in African capitals, as has a trade imbalance that enabled China to extract and consume raw materials from Africa while exporting finished goods that stifle domestic production and commerce.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa echoed the concern of many African leaders when he raised the topic of his country’s trade deficit with China and “the structure of our trade” during talks with Xi. In recent years, many African voices including scholars, civil society activists and even government officials have spoken of the need to create “balance” in Africa-China relations.

For them, the expanded relationship with China may have brought mutual gain but at a heavy, inequitable cost, particularly in the areas of trade and industrialization which African governments urgently need to transform the lives of their citizens. Many more Africans are calling for China to take major steps toward the realization of that goal like importing more African goods; building factories and industrial parks; and investing in domestic mineral supply chains, agricultural modernization and renewable energy.

It is unlikely that China will be able to meet all these expectations considering its own domestic challenges and priorities, which partly explains why African governments are expanding the range of their partnerships to include other actors like Turkey, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and South Korea. But none possesses China's financial and geopolitical heft, which likely means that Beijing will remain Africa's primary international partner for the foreseeable future.

Africa’s big guns are still the apple of China’s eye

In recent times, Africa’s heavyweights have been the sick men of their neighborhood. Countries like Nigeria, South Africa, Angola, Kenya, Ethiopia and Egypt have been beset either by low growth rates or macroeconomic instability — or both — that has often adversely affected smaller, better-performing economies nearby.

But for China, its path to Africa evidently still runs through these regional anchors and for good reason. They have historically been among the largest African recipients of Chinese loans and as the biggest economies on the continent, they will play an important role in its economic integration.

Last week, Nigeria and China elevated their relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership after a bilateral meeting between Xi and his Nigerian counterpart, Bola Tinubu. The two sides signed a number of agreements including a $3.3 billion deal to develop an industrial park and a memorandum of understanding to expand the Lagos Rail Mass Transit.

South Africa established an “all-round strategic cooperative partnership in a new era” with Beijing. Kenya formally joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, China’s alternative to the World Bank. Ethiopia, one of Africa’s biggest beneficiaries of Chinese industrial cooperation, signed a currency swap agreement aimed at reducing Addis Ababa’s reliance on third-party currencies for bilateral trade.

Beijing’s message to Africa at FOCAC 2024 was simple: size matters.

The curious case of Angola at FOCAC 2024

Angolan President João Lourenço’s absence from the Beijing confab was noteworthy, as the head of state of one of China’s key African partners. Some commentators speculated that it was linked to Luanda’s expanding relationship with the United States.

In recent years, U.S. officials have described Angola as a model for what they say is the “reset” of Washington’s relations with African countries. Since the 2022 U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, the two sides have hosted each other in bilateral engagements including a meeting at the White House in November 2023 between Lourenço and U.S. President Joe Biden.

Meanwhile, relations between China and oil-rich Angola have also gone through something of a rough patch lately over issues related to the so-called Angola Model, in which Luanda took oil-backed loans from China to fund infrastructure development projects in the aftermath of the country’s civil war.

Some of those ventures, like the Benguela Railway Rehabilitation Project and the installation of telecommunication networks across the country, have provided considerable benefit to Angolans. Others have not, even as some locals have accused Chinese firms of delivering substandard projects. Many Angolans have argued that the close relationship between Beijing and government officials from the ruling People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) party has fueled corruption in the country, particularly in state-owned firms like Sonangol, Angola’s national oil company.

Angola is said to be Beijing’s biggest African borrower, and reportedly owes a third of its debt to China. In recent years, Angola’s economy has experienced a downturn and it was one of the few African countries whose economy shrunk due to a COVID-induced recession. Angola received a three-year moratorium on its debt payment in 2020 but the resumption of the disbursements last year triggered another economic slump. Luanda reached an agreement with Beijing to ease — but, crucially, not cancel — its debt but Angola has nonetheless emerged as what some regard as an example of the excesses of opaque resource-backed loans many African countries take from foreign lenders.

It is possible that Lourenço skipped FOCAC because of Luanda’s desire to have closer relations with Washington, but it seems unlikely. For one, he visited Beijing in March when he signed an agreement with Xi that elevated bilateral ties between Angola and China to a comprehensive strategic partnership.

Moreover, the claim that Lourenço’s overture to Washington is a radical departure from the past is inflated. In reality, Angola has had solid relations with the U.S. since the early 1990s, when the MPLA renounced Marxism-Leninism in the waning years of the Cold War and established formal diplomatic relations with Washington.

The administration of then-President Eduardo dos Santos bowed to pressure from the Clinton administration as well as the World Bank and IMF to implement “Washington Consensus” policies that opened up Angola’s economy to more foreign participation. Large U.S. and Western oil companies like Exxon Mobil and the former Gulf Oil developed close ties with dos Santos and benefitted immensely from the neoliberal policies he pursued from the 1990s onwards. Relations between Luanda and Washington blossomed to the point that the Obama administration declared Angola in 2009 to be one of the United States’ three key strategic partners in Africa alongside Nigeria and South Africa.

By the same token, Angola’s relationship with China has never been as warm as many believe. It is a marriage of convenience that has been characterized by peaks and valleys that date back to the liberation struggle against Portuguese colonial rule. China was wary of the Soviet-backed MPLA and initially supported its rivals like the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) during the final years of colonization and the first years of the civil war that broke out after Angola won independence from Lisbon.

By the early 1980s, when the MPLA had gained the upper hand in the conflict thanks in large measure to Cuban and Soviet military assistance, Beijing announced its support of the MPLA, mostly as a face-saving measure intended to preserve Chinese influence in Angola. The relationship between the two countries has since improved significantly and China is now said to be Angola’s largest bilateral creditor. But it is by no means a hitch-free partnership, as the years-long friction between the two sides over debt, infrastructure projects and Chinese firms in Angola has indicated.

Lourenço’s reason for not attending FOCAC this year remains unclear. But it likely has little to do with a supposed entente with Washington. Whatever its rationale, Angola will continue to hedge between China and the U.S. and maintain cordial relations with both as it has done for more than three decades, an approach that many other African states have long mirrored. Relatedly, Lourenço has made little secret of his desire to raise Angola’s international profile amid the global race to secure partnerships with mineral-rich countries in Africa.

In the same year Angola will mark the 50th anniversary of its independence from Portuguese colonial rule, Lourenço will hold the AU’s one-year rotating chairmanship beginning in February 2025. Angola will host the U.S.-Africa Business Summit next year. Its favorable geography — underlined by a long Atlantic coastline and physical proximity to the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa — only adds to the geopolitical importance Angola holds.

Africa must define a tangible purpose for its future engagement with China

The latest edition of FOCAC came at a pivotal moment in the relationship between Africa and China as well as in global affairs more broadly. It took place two months before the 2024 U.S. presidential election, a contest whose outcome will shape global politics for the next four years and likely beyond.

While strategic competition among the world’s traditional powers is sharpening and their jostling for influence undoubtedly affects their respective relationship with Africa, other poles of geopolitical influence are emerging. Africans are increasingly assertive about their desire for the continent to be a pivotal actor in international affairs, and major powers like China and the U.S. are reckoning with their demands for a larger role in the emerging global order.

African demands for more and better representation within international institutions appear to be making some impact. Last year, the AU joined the G-20 and the membership of BRICS was expanded to include Egypt and Ethiopia. The ongoing effort by African states and the AU to get two permanent seats with veto powers on the U.N. Security Council in line with the Ezulwini Consensus gained some momentum with a report that the U.S. will back the creation of two permanent seats for Africa. But Washington’s opposition to expanding veto power beyond the members which currently hold it is unlikely to go down well in the U.N.’s Africa Group.

Ties between China and African nations, fruitful and productive as they have generally been, are not without their deficiencies. Nearly 25 years after the establishment of FOCAC, the relationship is due for an adaptation to modern conditions that include a rapidly evolving global landscape that the two sides must contend with. For Africa to better utilize its ties with China in the next phase of the partnership, the continent’s governments must better define the nature of the relationship and link it not only to their broader engagement with the globe but to their domestic objectives as well.

The era of African governments viewing China as a mere funder of checklist items that incumbent administrations and ruling parties build (re)election campaigns around must come to an end. Instead, they must connect the foreign partnerships they pursue to developmental objectives around mass employment, poverty reduction and human development.

African governments should view the uncertainty about the direction of Africa-China ties as an inflection point and opportunity, and not solely as a risk to their electoral prospects. This effort should begin with taking more ownership of the responsibility to set an agenda for the relationship with China. A quick glance at the public documents released before and after this year’s FOCAC summit would make clear that China is the main driver of the partnership, with Africa relegated to the status of a junior partner. The AU’s website contains next to nothing about FOCAC or Africa-China relations.

Even recognizing the power imbalance that exists in the relationship, African nations are not hapless victims with zero autonomy and should not think of themselves in that way. But they must have a plan of action for dealing with China. Contra many broadcasts that fill up African digital spaces on WhatsApp, Facebook and other social media platforms, China is not “colonizing” Africa, trapping the continent with debt or any such claims that have been popularized by Western governments, media organizations and commentators. But the flowery claim that it is “Africa’s best friend” or somesuch is also farcical. Many downsides of Africa’s relationship with China exist and can be articulated without indulging in inane conspiracies, and many African citizens regularly do so. Their governments should take meaningful steps to fix these shortcomings.

Africans ought to think of China as neither friend nor foe but a rational actor operating in the pursuit of raw interest. This has not been and will not be a hindrance to pursuing a productive relationship, but it certainly means that Africans must understand the stakes in the relationship and how to approach it. That is the only way that the next phase of Africa-China relations can meet the goal of “modernization” that was laid out at last week’s FOCAC.