#GhanaDecides2024: Ghanaians will not miss the Akufo-Addo era

The story of Akufo-Addo's presidency is one of false starts, setbacks and dashed hopes

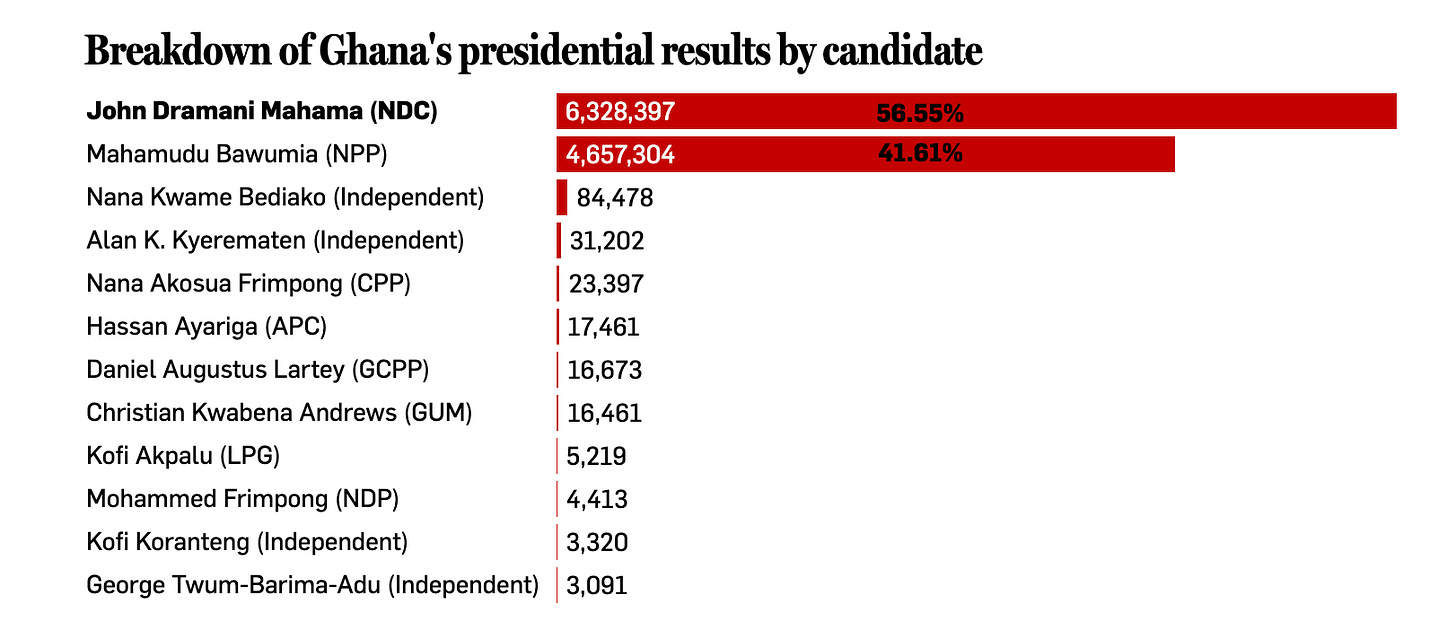

John Dramani Mahama, a former president of Ghana who served from 2012 to 2017, was declared by the country’s electoral commission as the winner of the 2024 presidential election. According to the Electoral Commission of Ghana, Mahama won 56% of the vote in the Dec. 7 poll, defeating 11 other candidates including Vice President Mahamadu Bawumia, his closest challenger who finished with 41% of the total ballots cast. Mahama’s running mate, Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang, will make history when she is sworn in as Ghana’s first female vice president.

The result completed Mahama’s remarkable comeback eight years after he lost a bid for reelection to Nana Akufo-Addo, who went on to serve two four-year terms as Ghana’s president and will step down in January. In an election that was largely a referendum on Akufo-Addo and his ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP), Mahama successfully tapped into the pervasive disenchantment among Ghanaians about their living conditions and the overall direction of the country.

The 2024 presidential election was essentially Mahama’s to lose, given Akufo-Addo’s unpopularity and a hesitance by voters to “break the eight,” a slogan referring to Ghana’s tradition of rotating the presidency between the two major parties after two uninterrupted four-year terms. Polls conducted in the runup to the election projected that Mahama would win the presidential race comfortably and his party, the National Democratic Congress (NDC), would win a significant majority in parliament.

In his victory speech, Mahama admitted that the ruling party’s unpopularity played a major role in the NDC’s electoral success, describing Akufo-Addo's presidency as “some of the darkest periods of governance” in Ghana’s history that “left a scar on our national psyche which may take some time to erase.”

Perhaps conscious of his loss in two of Ghana’s last three presidential elections including his failed bid in 2016 for reelection to a second term, Mahama said that the result of the 2024 poll “also serves as a constant reminder of what fate awaits us if we fail to meet the aspirations of our people and govern with arrogance.” By acknowledging that “there is much to do to salvage our country” including “severe measures” aimed at getting Ghana’s economy back on the right track, Mahama sought to manage sky-high expectations that lie ahead of his inauguration. He is unlikely to get that leeway from the voters who just gave his party a resounding mandate to run the country for the next four years.

Scratching beyond the surface of the election’s numbers

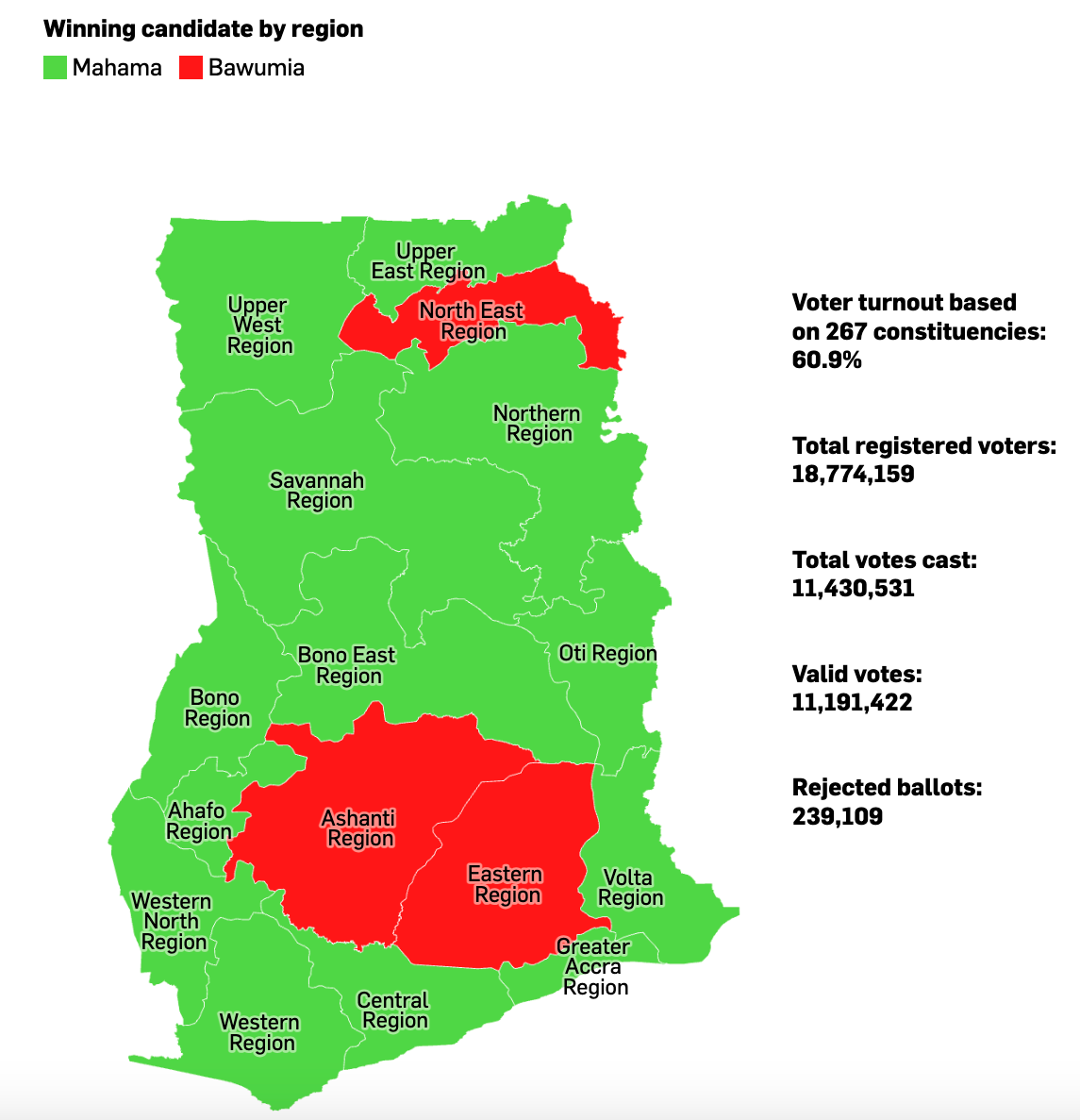

Mahama’s margin of victory in the 2024 presidential election was the largest by a winning presidential candidate in 24 years. He ran up the score in traditional NDC strongholds like the Volta and Upper East Regions and decisively won battlegrounds like Greater Accra, Western, Central and the three Regions of Ahafo, Bono and Bono East that make up the former Brong Ahafo.

In the NPP’s heartland of Ashanti and Eastern, Mahama registered his best performance in any of the four presidential elections in which he ran, becoming the first NDC presidential flagbearer to win more than 30% of the vote in Ashanti since 1996. The party’s parliamentary candidates in the Region also made impressive gains of their own, validating the effort made by NDC leaders to grow its support in the ruling party’s core territory.

Eligible-voter turnout in the 2024 election, which stood at a little over 60%, fell by a whopping 18 percentage points from four years ago, dropping to the lowest rate since 2000. There were approximately 2 million fewer votes cast in this year’s presidential race than in 2020, despite roughly 1.7 million more voters having registered for the 2024 general election. In Ashanti, voter turnout was said to have dropped from 83% four years ago to 56% this year. In the Volta Region, turnout fell to 60% in 2024 compared with 79% four years ago.

Some Ghanaian analysts blamed lower turnout on voter apathy amid the worst economic crisis in decades and reduced trust in public institutions. In addition, many voters felt that they were presented with an unappealing choice of candidates. Bawumia, the sitting vice president who was hampered by Akufo-Addo’s low approval rating, struggled on the campaign trail to distinguish himself from his boss while his proposals to digitalize the Ghanaian economy and expand Akufo-Addo’s ‘Free Senior High School’ (Free SHS) initiative did not seem to catch on with the electorate.

Mahama, who was the NDC’s presidential candidate for the fourth election in a row, is a former president, vice president, minister and member of parliament who has been a prominent figure since the mid-1990s. Viewed from that prism, his framing of his 2024 campaign as one of “change” and competence in managing state affairs rang hollow to many Ghanaians who duly noted that he was booted out of office eight years ago precisely because voters believed that he did not deliver the change and competence he promised in 2012.

The fact that both major-party candidates are from Ghana’s north and Bawumia was the first NPP presidential nominee to come from outside the Twi-Akan ethnolinguistic base that makes up the core of the party’s support might have played a role in the low turnout of voters in the vote-rich Ashanti and Eastern Regions. To some others, the seemingly foregone conclusion that Mahama would cruise to victory might have depressed turnout while many voters believed that the lack of a compelling “third force” presidential candidate caused many young Ghanaians to stay home on Election Day.

Ahead of the vote, two independent candidates, Alan Kyerematen and Nana Kwame Bediako, gained considerable attention from domestic and international media. Some foreign analysts thought that Bediako, a businessman who portrayed himself as representing Ghana’s disaffected youths and sought to appeal to them with messages of capitalist prosperity and pan-African renaissance, could draw enough votes from the two main candidates to force a second-round runoff. In the end, he did not cause a dent in their support and Bediako and the remaining challengers earned a little over 1% combined of the total vote.

All the aforementioned factors—and possibly others as well—likely played a role in the drastic drop in voter turnout in the 2024 election. But the clichéd “voter apathy” narrative does not provide much useful insight about why more than 7.3 million voters who registered for the 2024 election chose not to cast a ballot, given that turnout rates in previous elections have regularly reached north of 80%. In the coming months and years, that is a question Ghanaians will need to provide answers to but blaming voters for not being sufficiently enthused by the choices presented to them does not count as one.

Nana, Hey Hey Hey Goodbye

In an election that was a referendum on Akufo-Addo’s eight years in office, widespread dissatisfaction over the NPP’s economic record and public anger over corruption and mismanagement associated with the ruling party meant that Bawumia was all but certain to go down in defeat. Put another way, voters appeared ready to turn the page on the Akufo-Addo era and their verdict on his legacy was a resounding thumbs down.

This outcome is a far cry from the euphoria that ushered Akufo-Addo into Jubilee House in January 2017. Few presidential candidates in Ghana's history could match the pedigree of Akufo-Addo, who counted three of his relatives including his father Edward among the so-called Big Six who formed Ghana’s first political party, the United Gold Coast Convention, and are regarded as the country’s founding fathers. Akufo-Addo came to national prominence in the 1970s as a human rights lawyer who campaigned against military rule. He was instrumental in the NPP’s founding in 1992, when Ghana adopted its present-day constitution and held multiparty elections that ushered in its current Fourth Republic.

A former justice and foreign minister in the administration of then-President John Kufuor, Akufo-Addo lost two consecutive bids for the presidency in 2008 and 2012 before prevailing in 2016. Akufo-Addo’s case was bolstered by his message of experience, competence and integrity which voters believed made for a favorable contrast with Mahama, whose popularity was hobbled by a sluggish economy, a debilitating energy crisis and corruption scandals.1

Akufo-Addo’s 2016 campaign, powered by foreign consultancies like StateCraft Inc and 270 Strategies, was considered a watershed in Ghanaian electoral politics due to the resourceful social media operations and get-out-the-vote tactics it deployed on behalf of a stodgy septuagenarian who went from losing the 2012 election by a little more than 325,000 votes to winning the presidency by 9 percentage points four years later. That election, which marked the first time an incumbent Ghanaian president was defeated, was in keeping with a regional milieu of the 2010s in which opposition candidates in Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Gambia, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Senegal defeated sitting presidents or candidates nominated by the ruling party.

Upon taking office, Akufo-Addo launched domestic initiatives like the Free SHS policy to demonstrate an eagerness to fulfill his campaign pledges. On the international front, he quickly gained esteem particularly in the West for his “Ghana Beyond Aid” agenda that implored Ghana and other African countries to become more self-reliant and structurally transform their economies from a dependence on natural resources. Year of Return, an initiative Akufo-Addo launched in the United States to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved Africans in Virginia and promote diaspora investment and resettlement in Ghana, won plaudits for what its supporters saw as a tangible effort to boost the inflow of international tourists to Ghana and promote pan-Africanism.

By the fourth quarter of 2019, Ghana recorded a growth rate of 7.9% and was described by the World Bank as the fastest-growing economy in the world. The perception that Ghana was on the right track, despite several controversies linked to Akufo-Addo’s administration, was enough to secure his reelection in 2020 with 51% of the vote.

Akufo-Addo’s second term proved to be far more difficult and would go on to shape his legacy, which is likely to be defined by Ghana's worst economic downturn in years, a debt default and a bailout by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Inflation, which hit a record 54% in 2022 and currently stands at 26%, has pushed up the cost of food, fuel and transportation. This year, the Ghanaian cedi has depreciated by nearly 20% against the U.S. dollar. The unemployment rate has doubled in the eight years of Akufo-Addo’s presidency and joblessness is particularly acute for young Ghanaians.

Controversial measures like the construction of a national cathedral and the Electronic Transfer Levy (e-levy), a tax imposed by the government on digital transactions, signaled to Ghanaians that Akufo-Addo’s priorities were misplaced and he was indifferent to their suffering. Year of Return turned out to be less of a comprehensive plan to attract productive investments or revamp Ghana’s tourism sector, and more of a marketing device with which Akufo-Addo used to launder his international image and boost Ghana’s inflow of foreign exchange. Meanwhile in cities like Accra, where a quarter of the population lives on less than $1 a day, locals have had to deal with an explosion in living costs triggered by the inflationary effects of an increasingly dollarized economy driven by the influx of holidaymakers, resettlers and so-called digital nomads.

Akufo-Addo and his administration’s officials have frequently blamed Ghana’s economic downturn on the twin shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Their claim is not entirely without merit, but many Ghanaians quite reasonably pointed to the government’s own record of mismanagement, corruption and poor policymaking as contributing factors that worsened their living conditions. The increased economic hardship that would define Akufo-Addo’s second term resulted in recurring demonstrations like #FixtheCountry, #AriseGhana and #OccupyJulorbiHouse that snowballed into protests against poor governance in Ghana.

The gold and cocoa industries which employ a large segment of the labor market and account for a significant portion of Ghana’s export earnings have been hit hard by a mixture of domestic and international factors. Ghana’s cocoa output has been affected by bad weather, swollen shoot disease, a scarcity of agricultural inputs and the smuggling of beans across its borders. Illegal gold mining, known locally as galamsey, costs Ghana billions of dollars in lost revenue and is leaving behind devastating environmental impacts.

Its spillover effect is also noticeable in the agricultural sector, where contaminated freshwater is hindering the ability of farmers to grow and sell their crops. Ghana’s Forestry Commission estimated that 34 of the country’s 288 forest reserves have been negatively impacted and more than 100,000 acres of cocoa farms destroyed through galamsey operations.

During a visit to Côte d'Ivoire earlier this year, I embarked on a road trip east of the country’s border to Ghana’s Western Region and spent time in communities like Samreboi, Tarkwa, Daboase and Nkroful, best known for being the birthplace of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president. There, I heard many stories about—and saw for myself—the devastating toll that illegal gold mining, climate change, crop disease and surging cocoa and gold prices are taking on the welfare of people in local communities. Outrage over galamsey operations and adverse conditions for cocoa farmers triggered protests as recently as August and October. Akufo-Addo’s administration has been accused of incompetence, negligence and even complicity amid its failed effort to tackle illegal gold mining in Ghana.

A recent article in The Africa Report which stated that Akufo-Addo’s legacy is “IMF, galamsey, education” might have been on to something.

The Rawlings factor

Since 2020, when the first of several recent military coups hit the West Africa region, I’ve found myself thinking much more about Jerry John Rawlings, Ghana’s longest-serving head of state who dominated its politics through the 1980s and 1990s. Having come to prominence as a young, revolutionary military officer who overthrew the regime of General Fred Akuffo in 1979, Rawlings gradually “metamorphosed” into a civilian leader who oversaw Ghana’s transition from military rule to multiparty democracy.

His influence would spread well beyond Ghana’s borders, with many others in the region—particularly in Nigeria—holding out hope that their own “Junior Jesus” would emerge to bring their country back from the abyss. As part of a decade-long wave of West African military officers like Niger’s Seyni Kountché, Liberia’s Samuel Doe, Guinea-Bissau’s João Bernardo Vieira, Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara and Nigeria’s Muhammadu Buhari who seized power in the throes of a regional drought, economic hardship, protracted political crises and Cold War machinations, probably only Sankara went on to inspire more devotion among successive generations of West Africans than Rawlings.

Rawlings’ death in 2020—merely three days after the passing of Amadou Toumani Touré, another foundational officer-cum-politician in the region—in the middle of the 2020 election campaign and months after the 2020 Malian coup would underscore for many West Africans their belief that the path to a better future had different routes and one of them just might require the diligence of a soldier who was unafraid of breaking as many eggs as needed to make a sufficiently large omelette.

As the protagonist of Ghanaian politics for two decades and considering the pivotal role he played in laying the foundation of the current Fourth Republic, it would not be too hyperbolic to describe Rawlings as the founder of modern Ghana, as one of its online outlets described him in 2021. If Nkrumah was the defining figure of the first era of Ghana’s post-independence history, Rawlings is unquestionably the main character of the post-June 4th Revolution epoch whose imprint on the Ghanaian state would linger long after he relinquished power.

Since Rawlings peacefully handed over the reins to Kufuor in 2001, it has become a cliché to describe Ghana as a “resilient” or “stable” democracy and a “bastion of stability,” among other worn-out platitudes used typically but not exclusively by Western commentators to exceptionalize the country.

Ghana has not had a successful coup since its return to civilian rule in 1993. It has held frequent elections every four years that have generally been regarded as free and fair. Polls are typically conducted with a sense of high-mindedness, as seen by Bawumia’s gracious concession to Mahama well before the electoral commission declared a winner of this year’s presidential election. The country has a history of successful political transitions and since the dawn of the Fourth Republic, its presidency has alternated between the two main parties—NDC and NPP—every eight years.

Turnout rates in Ghanaian elections tend to be among the highest in Africa, and its polls tend to win the plaudits of international observers for their credible conduct. Ghana has a relatively open press, a thriving civil society landscape and hosts large numbers of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants from other parts of West Africa and the continent at large.

Akufo-Addo’s authoritarianism is a Rawlings legacy

Taken together, the temptation for outside observers—and many local ones too—to frame Ghana as a model democracy is understandable. But consider some of the global news events we have witnessed in the past few days:

a constitutional crisis in South Korea sparked by an unsuccessful attempt by President Yoon Suk Yeol to declare martial law;

the overthrow of former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the downfall of his family’s dynastic five-decade rule;

the collapse of the French government and the resignation of then-Prime Minister Michel Barnier;

Romania’s constitutional court annulled the country’s presidential election

These events demonstrated that “stability” as conceived by governments, pundits and armchair geostrategists is often contrived, subjective, ephemeral and not particularly based on deep, insightful knowledge of the world’s societies.

In Ghana’s case, the veneer of a stable constitutional order exhibited by regular elections, a network of civic organizations and a judiciary perceived to be independent masks the entrenchment of authoritarianism and other governance ills that run counter to the narrative of Ghana’s exceptionalism. Chieftaincy conflicts and their linkages to clientelist networks are a driver of violent instability in Ghana’s north. Vigilantes with strong but by no means exclusive links to political parties have long been a source of violence, including on Election Day.

The 1992 Constitution whose promulgation Rawlings oversaw legitimized a culture of executive dominance that his successors including Akufo-Addo have perpetuated. As noted by the Ghanaian legal scholar Maame A.S. Mensa-Bonsu, the requirement that a president choose most of their ministers from the legislature creates an incentive for them to divide and rule it, and empowers them to wield executive power as both a carrot and stick. Akufo-Addo was regularly accused of intrusion, including by a former attorney general who resigned his role as the country’s first-ever special prosecutor due to what he called Akufo-Addo’s “unconstitutional interference.”

In 2021, Akufo-Addo directed the then-auditor general to proceed on leave and replaced him on grounds that he had supposedly reached his retirement age. Ghana’s Supreme Court later ruled that Akufo-Addo’s decision was unconstitutional. In the two instances, as well as several others, he was widely suspected of usurping his powers to protect political allies and close relatives who were accused of corruption and other forms of malfeasance. A leaked letter written by Chief Justice Gertrude Torkornoo to Akufo-Addo, in which she recommended the appointment of five new justices to Ghana’s Supreme Court months before the 2024 election, resurrected longstanding accusations of Akufo-Addo’s tampering with the impartiality of the judiciary.

During Akufo-Addo’s presidency, security forces have regularly responded to anti-government demonstrations with brutality. Civil society groups documented instances when protesters were harassed, arrested, tortured and even killed by law enforcement. Akufo-Addo’s administration has refused to comply with an order to release critical information relating to a joint investigative report by the Economic Community of West African States and the United Nations on the enforced disappearance of Ghanaian nationals in Gambia during the regime of former President Yahya Jammeh. In the run-up to this year’s election, Akufo-Addo and other NPP stalwarts heightened tensions with inflammatory language that raised questions in the minds of voters about the trustworthiness of key state institutions like the electoral commission, judiciary and security organizations.

It would be easy to blame Akufo-Addo for the weakening of Ghana’s civic institutions as well as declining public trust in them, and there is no question that he bears responsibility for the events that transpired during his presidency. But to personalize Akufo-Addo's overreach would be missing the structural forest for the trees of individual agency. It is impossible to disconnect the authoritarianism of Akufo-Addo and his predecessors from the imprint Rawlings laid down during his long rule.

NDC, the party he founded to complete his transition into a civilian president, was essentially a reinvention of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), the dictatorship Rawlings established in 1981 to implement what he called “the highest form of democracy.” As domestic and international pressure grew for Rawlings to restore civilian rule in Ghana, he established the NDC as a social democratic party inspired by the workers’ and defense committees he created under the PNDC.

Their repressive antecedents were enshrined in the political order that the 1992 Constitution ushered in and many of them were deepened by Rawlings’ predecessors. Despite meaningful improvements brought about by litigation in the post-1992 era to curb some of their excesses, many Ghanaians believe that the current constitution must be amended to constrain the excesses of presidential overreach and arbitrary power that they believe it embalmed.

The task ahead for Mahama and the NDC is huge. Economic anxiety is widespread and poverty is increasing, despite some recent signs of macroeconomic growth. Ghana’s international partners, including the IMF, will be paying close attention to the appointments Mahama makes to economic portfolios including the all-important finance ministry.

Having won the presidential race in a landslide and secured a two-thirds majority in parliament, the NDC can reasonably claim to have a mandate to implement far-reaching measures needed to improve the livelihoods of Ghanaian citizens. Constitutional reform is one of the items many of them believe the incoming NDC-led government must prioritize. Following the party’s resounding win in the Dec. 7 election, some of its stalwarts have committed to amending parts of the constitution to fix its perceived shortcomings. For his part, Mahama has pledged to learn from the drawbacks of his first term and run a leaner, more accountable government in a second administration.

These pledges are welcome, and following through with inclusive, consultative processes would be even better. Quick solutions to protracted challenges on thorny issues like the economy, security, corruption, health care and illegal mining will likely not emerge quickly, and may not even exist at all. In that case, tradeoffs that might upset key, influential allies might be necessary. Those scenarios will produce some of the biggest stress tests of Mahama’s leadership, as well as his claim to have been chastened by his years out of power. Given the outsized expectations which Ghanaians have, they will be expecting a quick demonstration of the seriousness with which he pledged to govern in his second term.

Sounds familiar?