Some observations on the South African general election

Democracy is not dying in Africa, the ANC believed its own hype, international reaction to #SAvotes2024 and much more

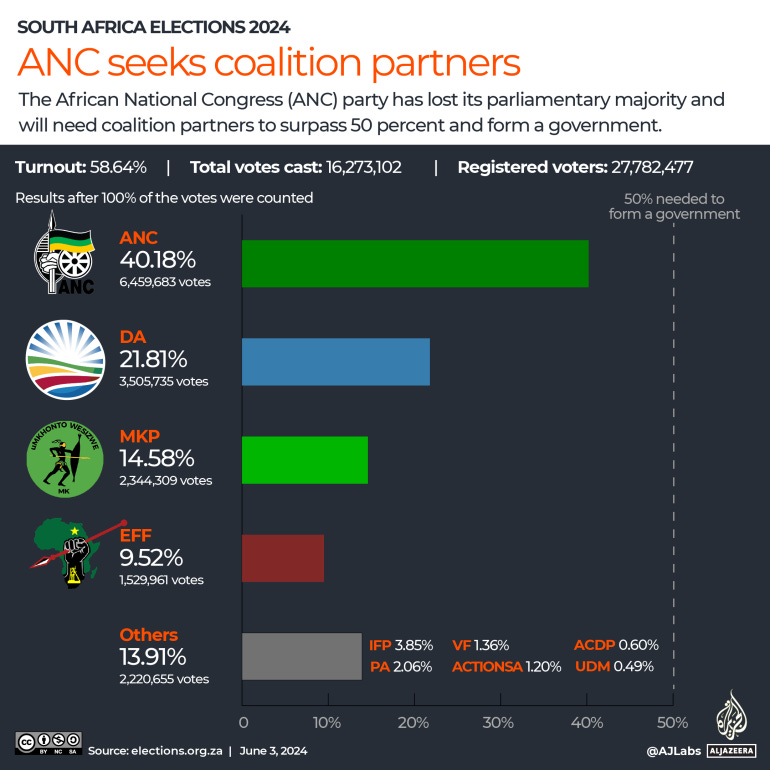

South Africa’s political parties are locked in talks to form a new government after none of them received enough votes to secure a majority in the 2024 general election.

On June 2, South Africa’s electoral commission declared that the governing African National Congress got 40% of the vote in this year’s poll, a 17-percentage point decline from the last general election in 2019. In doing so, the ANC lost its parliamentary majority for the first time since it gained power in 1994.

This year marked the party’s worst electoral performance since it was ushered into office three decades ago in a watershed election that symbolized the formal demise of apartheid. Although the ANC still had the single largest share of votes cast in the 2024 election, its failure to get more than 50% of the vote total meant that it will not have a majority in the National Assembly for the first time since the landmark 1994 election.

As a result, President Cyril Ramaphosa — who dual-hats as the ANC’s leader and South Africa’s head of state — has invited the country’s political parties to enter talks with the ANC to form what he calls a government of national unity. They must hash out an agreement before June 16, when the two-week window between the announcement of the election results and the first sitting of the newly elected parliament will close. South Africa’s chief justice has announced that that convocation will take place on Friday, adding to the urgency to form a government before then.

The 2024 election was a milestone in South Africa’s political development. Prominent government ministers including Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor, Defense Minister Thandi Modise and Bheki Cele, the minister of police, were turfed out of parliament on the heels of the ANC’s underperformance at the polls.

For several years, the ANC’s declining popularity among the electorate had been apparent to many observers. With voters growing more frustrated with longstanding problems of widespread corruption, unemployment, high crime rates, social inequality, declining public services and a devastating energy crisis, some believed that the ANC was due for a reckoning.

The first major warning sign that this year’s election was unlikely to be business as usual arguably came three years ago in the 2021 municipal election, when the ANC dipped below 50% of the vote in a nationwide contest for the first time since 1994.

Not unrelatedly, 52 political parties and 11 independent candidates filed to contest South Africa’s most anticipated vote since its first democratic election in 1994. Several polls conducted in the runup to the May 29 election projected that the ANC’s share of the vote would fall to 45%, below the 50% threshold required to form a government by itself. But by plummeting to 40%, the ANC performed even worse than expected in what can only be described as a sharp rebuke of the once-revered party that was birthed in South Africa’s liberation struggle against white-minority rule.

The details of South Africa’s 2024 election will be debated for months and years to come, and the vote’s broader ramification will be determined by the course of history. For now, though, here are four non-exhaustive observations on last month’s vote.

South Africa is a useful corrective to the “democracy in Africa is dying” narrative

It bears repeating that elections alone do not make a democracy, much less one that is inclusive and accountable. And the conduct of a generally free, fair and credible vote in which the governing party performs poorly does not preclude the possibility that other obstacles to civic engagement and accountability exist. But elections are nonetheless significant as one measure of the pulse of the citizenry, and the norms and principles that underpin the franchise are priceless.

In that vein, it was useful to see Ramaphosa and the ANC’s top brass publicly — and immediately — accept the declared results of the May 29 election and verbally acknowledge the disillusionment that presaged the shellacking their party received from voters. It was certainly more than could be said for the United Statessome other large, English-speaking former settler colonies that are also scheduled to hold elections this year. Credit also goes to most of the other parties and their leaders which also upheld the spirit of sportsmanship by accepting the verdict of voters1.

Given South Africa’s prominence and visibility on the continent, its ability to conduct a credible election process was a valuable corrective to the “death of democracy in Africa” nonsense that has gained currency in recent years amid a worrying number of military coups on the continent. The threats to democratic governance in Africa are undoubtedly real and tangible but far too often analysts mistake symptoms for causes.

The military takeovers seen across the continent, with few exceptions, have taken place in former French colonies in West Africa with fragile, coup-prone states that have long been incapable of imposing any kind of social order. When viewed more broadly, the evidence for claims of a “return of military coups” or that Africans are turning against democracy is weak if it is measured against well-defined yardsticks that can be tested empirically across the continent’s 55 countries.

It makes no sense to lump together societies as varied as Ghana, Chad, Tanzania and Botswana in sweeping, context-free statements about “democracy in Africa,” and South Africa’s election was a useful reminder of why.

The ANC believed its own hype

The possibility that the ANC could someday fail to command an electoral majority in a general election was not exactly a fringe notion, but few observers expected that the party would sink to its current low so quickly.

In subsequent elections after the landmark 1994 poll, in which the ANC secured 63% of the vote, the party raised its share of the vote, peaking at 70% in 2004. Although that was a high-water mark for the ANC that it has not matched since, the party nonetheless won large majorities in 2009, 2014 and 2019, when it took 57% of the vote in what was regarded at the time as a weak performance by its stratospheric standards.

In the three decades since the ANC swept to a euphoric victory in South Africa’s first non-racial election, its hold on power seemed unassailable to most observers of the country’s politics including the ANC’s leadership. Commonly described as “Africa’s oldest liberation movement,” the ANC is a societal leviathan with tentacles in virtually every corner of a country that holds its icons like Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu and Albert Luthuli in saintlike reverence.

The memory of the ANC’s moral leadership in the struggle against apartheid and its genuine — if insufficient — effort in its first decade in power to lift millions out of poverty was usually enough to win dominant electoral majorities. That voters, including the ANC’s core supporters, came to believe that the party’s elites had abandoned the promise of social justice and representative government laid out in its Freedom Charter in favor of narrow self-enrichment seemed to belie the solid mandates they gave to the ANC every five years.

Despite many internal difficulties particularly during the eras of Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma, the party and its Congress allies demonstrated time and again that they could withstand major shocks to the ANC’s supremacy. The party appeared to believe, a la its onetime foe Margaret Thatcher, that there was no real alternative to its hegemony. Evidently voters in 2024 demonstrated that they did not believe that to be the case, if at all they ever did.

The realization that the public was in a mood to deliver a strong rebuke to the ANC came as a shock to its leaders as well as to international media, as seen in several headlines including one from The New York Times that declared that South African voters rejected “the party that freed them from apartheid.”

The “international community” showed particular interest in South Africa’s election — and it took a side.

The attention paid by international media to South African’s election struck me as more pronounced than usual, and considerably more than is typically given to African elections. Much of that spike in foreign interest was spillover from the 30th anniversary of the 1994 vote, which commanded global attention at the time not just for its historical implications but also the fear that the election would be scuttled by a white far-right cohort determined to violently abort the transition from apartheid to non-racial democracy.

The possibility that Mandela's party, which swept to power in that election, could lose the parliamentary majority it had held since 1994 also made for a tantalizing plot twist that seemed too good to ignore. Then there is the longstanding framing of South Africa as a Western outpost in Africa — a common trope used by South Africa’s apartheid-era regimes to win the West’s support that perseveres today — that appeals to international media sensibilities.

But those considerations paled in comparison to the election’s potential geopolitical implications. South Africa’s post-apartheid relations with the Global North have been cordial at best but lately the country is regarded by Western powers as a bête noire. After the breakout of war in Ukraine, Tshwane (Pretoria) came to symbolize what the U.S. and its European allies regarded as an unacceptable moral relativism by African governments in the face of a conflict they saw as a peripheral concern but which many Western capitals viewed in existential terms. A series of separate but related disputes linked to South Africa’s relations with Russia exacerbated tensions between Tshwane and Washington last year.

South Africa's opposition to Israel’s war in Gaza and the genocide case it is pursuing against Israel at the International Court of Justice have added new layers of tension to South Africa-U.S. relations. Elsewhere, Tshwane is a leading champion of the expansion of BRICS, which it views as a means of counterbalancing Western dominance of the global financial architecture.

During the early onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Ramaphosa played a crucial role in the African Union’s COVID-19 response and was a vociferous critic of the “vaccine nationalism” among wealthy, industrialized countries. He has also advocated for climate justice for African countries and echoed calls by the continent’s leaders for reforms of the global financial architecture.

The positions on key foreign policy issues Tshwane has taken have led some in the U.S. to support calls for a “review” of the bilateral relationship, a demand Republican lawmakers in the U.S. Congress have taken up. Others have floated the possibility of revoking South Africa’s trade privileges under the African Growth and Opportunity Act, or AGOA, a law intended to facilitate duty-free export of African goods to the U.S.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Alliance — South Africa’s white-led largest opposition party — generally opposes core planks of the South African government’s foreign policy. The party is against BRICS, its leaders are pro-Ukraine and anti-Russia and the DA maintains a broadly pro-Israel stance that includes support for a two-state solution.

The DA has a formidable overseas presence particularly in Anglosphere nations like the U.K. and Australia — where hundreds of thousands of white South Africans have emigrated since the waning years of apartheid — and typically wins the South African diaspora vote. Ahead of the 2024 election, the DA stepped up its lobbying operations in the U.S. to build sympathy for its cause there. Broadly speaking, its message to influential opinion-makers in Western capitals like London and Washington was essentially the same as its pitch to South African voters: That it was on a mission to “rescue South Africa” from three decades of (Black) ANC rule.

With pre-election polls showing that no party was likely to win a large enough majority to form a government, the DA based much of its campaign around scaremongering against a “doomsday coalition” that could potentially involve the Economic Freedom Fighters and uMkhonto weSizwe, two breakaway parties whose leaders split from the ANC.

Evidently, the DA’s charm offensive paid dividends as seen in the sympathetic coverage the party has received in Western media organizations before and after the election. The DA is frequently described in international commentary with favorable terms like “centrist,” “moderate” and “business-friendly” while the Black-led EFF — and its leader, Julius Malema — is tagged as “radical,” “leftist,” “divisive” and “populist.”

In an op-ed published the day after South Africa’s electoral commission declared the results of the 2024 election, the Washington Post’s Editorial Board called for a grand coalition between the ANC and “the moderate Democratic Alliance,” whose praises the op-ed’s writers sang while castigating Malema and the EFF with hysterical turns of phrase like “red beret-wearing firebrand.” The Economist and the Wall Street Journal, the holy bibles of Anglo-Saxon neoliberalism, echoed that call for an ANC-DA government.

Some other commentators hid their preference for a role for the DA in the next South African government behind a veneer of concern about “the rand” and what “the markets” and unnamed “investors” want to see. Apparently, “markets” and “investors” are neutral, rational and omniscient phenomena that exist beyond human control and judgment. To the DA’s international and domestic sympathizers, the party is the adult in the room needed to steady South Africa’s sinking ship.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but “moderate” and “centrist” are strange words to describe a political party whose modern foundation comprises remnants of the reactionary National Party that was responsible for the implementation of apartheid rule in South Africa. While it is true that the DA’s roots lie partly in white liberal opposition to apartheid, that tradition isn’t nearly as venerable as some revisionist history might suggest.

The DA is viewed by Black South Africans as an elitist party that caters to white economic interests, a perception that has only intensified with the party’s purge of senior Black members from its ranks. More to the point, the DA — which made a calculation to capture the now-defunct National Party’s voters with a sharp turn to the right — engages in some of the ugliest race-baiting in modern South African politics as seen in an election campaign video that depicted the burning of the South African flag, a staple of white far-right groups in the country. It has lent authority to the “genocide of white farmers” conspiracy theory that was previously the domain of white supremacist websites and forums until former U.S. President Donald Trump gave it mainstream credibility.

The DA embodies a more strident form of the market fundamentalism that has characterized the three decades of ANC rule. It opposes efforts to redress South Africa’s racialized inequalities like minimum wage laws, a recently passed national health insurance law and the ANC's Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment policies.

Last year, DA’s leader John Steenhuisen appallingly appropriated the vocabulary of the ANC’s 1950s Defiance Campaign against apartheid rule in a speech that laid out his party’s opposition to what he called “ANC race laws.” Helen Zille, the party’s former leader, caused a firestorm several years ago when she praised South Africa’s colonial legacy. If this is what characterizes a “centrist” and “moderate” party, then that speaks to the hollowness of these terms as a useful measure of political ideology.

Coalitional politics might not necessarily improve governance in South Africa

Many analysts are pondering what the results of last month’s vote mean for South Africa’s politics. At first glance, it does appear that the ANC’s seemingly impregnable dominance of the electoral landscape is a feature of the past. At the same time, the ANC remains South Africa’s largest party and is likely to be the dominant party in government for the foreseeable future even if coalitions become the norm going forward.

Some observers, including many South Africans, believe that a new era of coalitional politics at the national level will impose much-needed checks and balances on the ANC and generate new ideas needed to resolve the country’s numerous challenges. But if the history of multi-party rule in South Africa’s provinces — or in Europe for that matter — is an indication, it is just as likely that coalitional governance in Tshwane will bring what one South African scholar described as “static equilibrium.”

Say this for Ramaphosa, it is quite the twist of fate that the man who, as one of Mandela’s trusted lieutenants, was the ANC's lead negotiator during the talks that led to South Africa's democratic transition and took up the reins in 2018 to clean up the party after the tumultuous Zuma years led the ANC to its worst electoral showing to date. That man is now faced with the prospect of heading South Africa’s second government of national unity since 1994.

Unlike three decades ago, when the Mandela-led coalition was a condition of the interim constitution drafted during the negotiations to formally end apartheid, Ramaphosa’s hands were forced by the outcome of the May 29 election. Given the sharp rebuke the Ramaphosa-led ANC received from South African voters and the longstanding grievances against the terms of the country’s negotiated settlement, Ramaphosa’s defining legacy just might be that of a man who took on thankless jobs he realistically could not deliver on and left everyone including his backers feeling unsatisfied.

One party which did not accept the outcome of the election is uMkhonto weSizwe, or MK, the six-month-old party led by Jacob Zuma, Ramaphosa’s predecessor as ANC leader and South Africa’s president. MK has informed the National Assembly of its intention to challenge the validity of the election results as declared by the electoral commission and boycott the first sitting of the new legislature.