Ruto is the West's man in Africa. Is that good for Kenya and the rest of the continent?

If Kenya is to play a role as a continental anchor, Nairobi needs to be more than a stalking horse for Western geopolitical machinations

Days after William Ruto was sworn in as Kenya’s fifth president, he told a session of the United Nations General Assembly that his country was “ready to work with other nations to achieve the pan-Africanization of multilateralism and a more just and inclusive system of global governance.”

When Ruto spoke to the U.N. General Assembly in September 2022, he seemed an unlikely ambassador of international norm entrepreneurship. For many years, he struggled to live down his alleged role in the violence that followed Kenya’s 2007 general election, for which he was charged by the International Criminal Court. The case was later dismissed due to insufficient evidence.

After he won Kenya's presidency, Ruto worked to convince foreign observers that he would let bygones be bygones. Thus, the Western powers which were initially skeptical of Ruto on account of his controversial past quickly embraced him at a time when they were worried about losing ground in Africa to their geopolitical rivals.

Under Ruto, Kenya has gone out of its way to reassure its traditional Western partners of Nairobi’s dependability amid their deepening nervousness about China’s extensive influence in Africa as well as the emergence of other foreign actors like Russia, Indonesia, Turkey, India, Brazil, Malaysia and Gulf states like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Qatar.

Since Ruto took office, he has hosted high-profile dignitaries like the U.K.’s King Charles III, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Kristalina Georgieva, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Earlier this year, Ruto made a state visit to the United States, becoming the first African leader in 16 years to do so. He has dispatched Kenyan security forces to lead peacekeeping missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Haiti, winning the approval of Washington and its European allies in both instances.

On other global peace and security issues like the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, Ruto has sided with the Global North while paying lip service to Africa’s tradition of nonalignment. His decision to skip last year’s Russia-Africa summit — ostensibly due to a desire for the African Union to represent the continent in international summits — found support in Washington and other Western capitals.

Although Ruto has downplayed the notion of a “Look West” foreign policy and insists that Kenya seeks friendly relations with multiple partners, it is indisputable that Nairobi’s relations with Western powers under his administration are characterized by a degree of fervor unseen in a long time.

But Kenya’s chumminess with the West has not yielded significant benefits for its citizens nor has the country's jostling for visibility greatly enhanced its influence on the continent. As for the role of Eastern Africa’s regional anchor that Nairobi considers to be its bailiwick, there is not much evidence that the Ruto administration’s foreign policy has generated more gravitas for Kenya today than it possessed two years ago.

Ruto’s jockeying for more prominence overseas has not improved his standing at home. If anything, it has sparked criticism from Kenyans who believe that the time he spends on foreign affairs should be focused on important domestic issues. This raises important questions of what Kenya has benefitted thus far from Ruto’s keenness to be the West’s point man in Africa and what it stands to gain in the long run.

If Kenya is to realize its ambition of playing a leadership role in Africa, its approach to foreign relations must be centered on producing impactful, sustainable benefits for its people and the continent more broadly, and less on currying favor with foreign powers for provincial reasons.

Kenya-France relations as a symbol of Nairobi’s global ambition

On the sideline of this year’s high-level week of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Ruto and his French counterpart, Emmanuel Macron, announced that Kenya will host the Franco-Africa Summit “Africa-France Summit” in 2026.

This will mark the first time since the gathering was launched in 1973 that it will take place outside France or one of its former African colonies. The break with precedent further illustrated Macron’s stated desire to put Paris’ relations with African nations on a new footing a la his discours de Ouagadougou in 2017.

Though the choice of a non-francophone country as the next host of the summit confounded some observers, its explanation is straightforward enough. Macron has made little secret of his desire to broaden France’s footprint on the African continent beyond its traditional spheres of influence in West, Central and North Africa.1 During his presidency, Macron has made high-profile visits to Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Angola, Ethiopia and Kenya in order to boost France’s ties with non-Francophonie African states.

The selection of Nairobi as the host of the next Africa-France Summit was also likely influenced by Ruto’s burning desire to showcase himself as an important statesman who can command global attention and project influence in Africa. It demonstrated his aspiration to place Kenya at the forefront of what his administration described as “Africa’s role in driving global solutions,” particularly on the issues of climate action and reform of the global financial architecture which Ruto and Macron have taken up as pet causes.

The personal diplomacy between the two heads of state is worth mentioning, as is their converging interest in climate change and global finance. They have struck up a strong relationship since Ruto took office in 2022 and the two men have tried to stake out a position as thought leaders on the intersection of climate governance and reform of the global financial architecture. To bolster their credibility on those issues, they have launched high-profile symposiums intended to bring together world leaders, diplomats, business executives, NGOs and other important personalities.

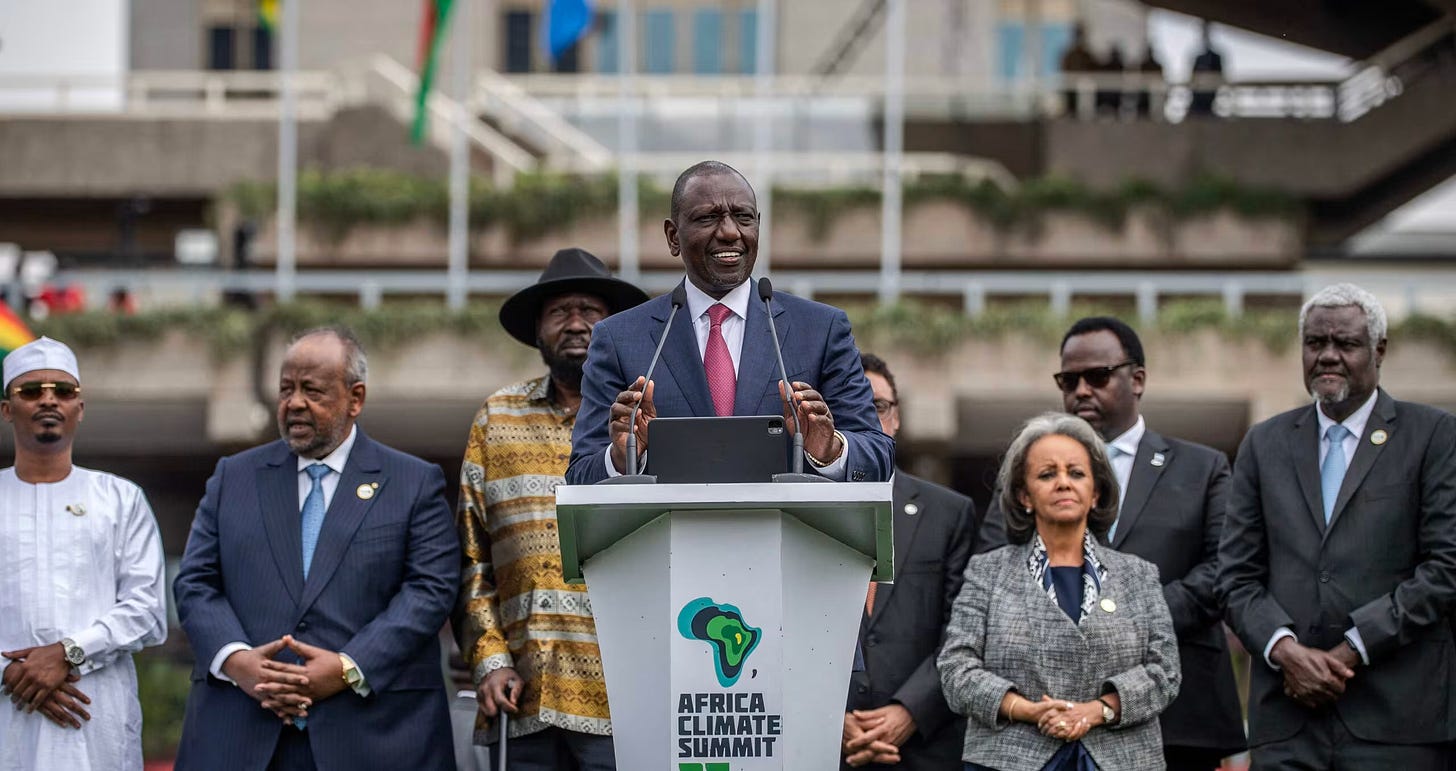

During his presidency, Macron has created the Paris Peace Forum and the Paris Pact for People and the Planet (4P) as mediums to address a list of global challenges. For his part, Ruto hosted the first-ever Africa Climate Summit last year in Nairobi, assembling more than 20 African heads of state and government as well as the leaders of international organizations like the UN, African Development Bank and European Union.

As the leaders of leading states on their respective continents, Ruto and Macron are eager to shape conversations and policies on climate, global finance and other major issues as they affect Africa and Europe respectively. Regardless of its motivation, the growing bonhomie between France and Kenya underscores the “clean slate” approach Paris says it is seeking on the continent. It also symbolizes Ruto’s pivot back to the traditional pro-West foreign policy Nairobi has generally maintained since it gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1963. Taken together, the two developments exemplify the ongoing renegotiation of the geopolitical order as well as the opportunities that global actors believe is available to them.

The case of William V and Uncle Sam

Decades after Mwai Kibaki launched Kenya’s “Look East” framework and his successor Uhuru Kenyatta consolidated it, Ruto has taken steps to reorient Nairobi toward Washington and its Western allies.

Having campaigned on an anti-China plank, Ruto has called for more U.S. investment in Kenya while keeping a healthy distance from Beijing. He maintains an unusually close relationship with Meg Whitman, Washington’s ambassador in Nairobi. Other top U.S. officials have visited Kenya recently including Trade Representative Katherine Tai; Gen. Michael Langley, the commander of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM); and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, who signed a five-year defense cooperation agreement with his Kenyan counterpart last year. Kenya joined Operation Prosperity Guardian, a U.S.-led multinational coalition created to protect commercial shipping in the Red Sea from a blockade by Houthi rebels in Yemen. In February, Kenya hosted Justified Accord, AFRICOM’s largest military exercise in East Africa.

On many critical domestic and foreign policy issues, Ruto’s administration has adopted positions that the United States favors. At a time when Washington is increasingly short on resolute Africans partners, his emergence as a friendly face is an encouraging sign to U.S. officials that their country can still project influence on the continent. In return, Washington rewarded Ruto’s steadfastness with the first invitation of an African leader to an official state visit since 2008. During that trip, U.S. President Joe Biden announced that his administration would designate Kenya as a major non-NATO ally, a symbolic move that nonetheless grants Nairobi privileged access to sophisticated military equipment, training and loans to boost its defense spending.

No less a stalwart defender of the U.S.-led “liberal international order” than the Financial Times raised important questions of the substance behind Washington’s embrace of Ruto. Decades of cooperation between Kenya and the United States has not ameliorated Nairobi’s domestic and regional security concerns, but it has enfolded Kenya in the vortex of Washington’s destabilizing Global War on Terror. The Biden administration abandoned a proposed bilateral free trade agreement that the Trump administration was negotiating with Kenya in favor of an opaque Strategic Trade and Investment Partnership which perpetuates the trade agreement’s deficiencies like its demand for Kenya to weaken its restrictions on genetically modified foods and directives protecting consumer rights. In Sudan, where a brutal 18-month war has potentially claimed up to 150,000 lives, the regime of Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan rejected Ruto’s appointment as the head of a quartet formed by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development to mediate the conflict. Nairobi’s broader attempts to broker peace in Sudan have been stymied by far more influential foreign actors like Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

While recognizing that Ruto’s presidency is young, the closeness he has developed with the United States has not given way to a boost in its bilateral trade and commercial relations with Kenya. Ruto's state visit did not unlock the investments he promised, and reports by Kenyan and international media of a “$3.6 billion highway deal” with a U.S. firm was a misleading interpretation of a statement which referred to “anticipated” investments but which contained no binding commitment to that sum.

Even the lighter elements of Ruto’s trip did not go as planned. His visit to Tyler Perry Studios did not yield a meeting with the founder of the eponymously named production studio while U.S. Speaker of the House of Representatives Mike Johnson turned down a request by top Democrats for Ruto to address a joint session of the U.S. Congress. The deployment of Kenyan troops to lead an East African regional force in Congo was a poorly-conceived mission that ended in ignominy when Kinshasa refused to renew its mandate past its expiry date of December 2023. Ruto's decision to send Kenyan police officers to support a U.N.-backed multinational mission to Haiti aimed at curbing violence there drew condemnation by many Haitians and Kenyans alike.

The increased attention Washington has showered on Ruto might represent an individual PR coup but it doesn’t appear congruent with what Kenyans want or need. That dissonance came to the fore during the #RejectFinanceBill protests that engulfed the nation earlier this year, when a nationwide uprising forced the Ruto administration to abandon punitive austerity measures that the IMF imposed on Kenya as a condition of its financial assistance. The United States’ backing of an international economic order which entrenches global inequality by creating cycles of crushing debt that force governments in developing countries like Kenya to spend more money on servicing their debts than they do on education or health is out of step with the paeans to mutual prosperity that government officials in Washington and Nairobi regularly recite.

It was befitting that the Biden administration published its memorandum designating Kenya as a major non-NATO ally on June 24, a day before the deadly protests that saw Kenyan security forces open fire on protesters. Considering Washington’s complicity in Kenya’s repressive national security apparatus as well as the anti-poor economic policies consecutive administrations in Nairobi have implemented, perhaps it is no wonder that Kenya was one of the three countries in Africa where U.S. approval ratings fell at the sharpest clip last year.

Ruto’s climate hustle signifies his hollow Pan-Africanism

Since he became Kenya’s president, Ruto has positioned himself as a Pan-African statesman who pushes the continent’s interests in international forums. He vocally champions climate change, debt relief and the reform of multilateral institutions. He has expressed verbal support for the dedollarization agenda and called for African countries to adopt the Pan-African Payments Settlement System. At a summit in Zambia, he called for additional reforms of the AU that would further empower the bloc. Ruto’s call for an end to the “summoning” of African leaders to so-called One-Plus-Africa summits and his announcement last year that Kenya would waive the visa requirement for African visitors both won widespread approval across the continent. Down to his sartorial choice of a “Kaunda suit,” Ruto consciously cultivates the image of a progressive African leader who can project influence on the continent and shoulder the burden of being its voice, or at least one of its most important ones.

Ruto’s signaling has not gone unnoticed by his continental colleagues, who have welcomed his seeming willingness to assume the responsibility of leadership. He currently serves as the chair of the Committee of the African Heads of State and Government on Climate Change (CAHOSCC). At last year’s COP28 conference in Dubai, he convened a gathering of African heads of state and senior government officials in which he launched the Africa Green Industrialization Initiative, which aims to accelerate and scale green industries across the continent. In February, the AU appointed Ruto to lead its institutional reforms process, inheriting the reins from Rwandan President Paul Kagame who had steered the union’s restructuring process since its inception in 2018.

The Confederation of African Football’s announcement that Kenya will co-host the 2027 Africa Cup of Nations with Uganda and Tanzania was another win for Ruto that could boost his political fortunes in a year he is likely to seek reelection to a second term. His climate diplomacy has resonated beyond Africa’s shores, as Time Magazine named him as one of the world’s 100 most influential leaders shaping global climate action.

One drawback of Ruto’s Pan-African posturing is that it is more stylistic than functional. Take his announcement that Kenya would waive visas for African tourists and business travelers, a move Ruto said was aimed at spurring continental integration and creating a borderless Africa. Kenyan authorities announced that from Jan. 1, 2024, all foreign nationals who wished to travel to Kenya for business or tourism for up to 90 days would no longer need a visa to do so. In lieu of a visa, Kenya created an Electronic Travel Authorization (ETA) which would require foreign travelers to pay the sum of $34, submit their flight and lodging details and wait for 72 hours to get approval to travel.

This new system is another visa regime in all but name and has proven to be far more burdensome for many visitors to Kenya than the previous one. During a panel discussion in May at the Africa CEO Forum in Rwanda, a country which actually runs a visa-free regime for African passport holders, the journalist Larry Madowo relayed the difficulties many travelers have found with Kenya's ETA but Ruto incredulously insisted that the new regime was visa-free.

Mirroring many other African leaders like Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo, Ruto has mastered the act of thrilling foreign audiences with superficially emancipatory pronouncements that appear to encourage African self-reliance and accountability. He tends to balance them out with the occasional rebuke of the Western-led international order, demands for an overhaul of its institutions and a framing of Africa as a place of “opportunity.” Like any good politician, Ruto tailors his message to the makeup of his audience and isn’t immune to contradicting himself even within the same set of remarks. But upon closer inspection, Ruto’s calls for African self-empowerment disguise his inclination for undermining African common positions and perpetuating foreign agendas that hurt the continent’s interests.

For instance, Kenya signed an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) last year with the EU that the East African Community (EAC) rejected, even as Nairobi was locked in disputes with neighbors like Uganda and Tanzania. The Kenya-EU EPA was criticized for conflicting with EAC protocols and going against the spirit of the AU’s regional integration agenda, which advocates for trade agreements to be spearheaded by the continent's Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and linked to the African Continental Free Trade Agreement. As a means of checkmating a major political rival, Ruto agreed to support former Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s bid to be the AU Commission’s next chairperson. There again, Kenya’s neighbors looked unfavorably on Odinga’s candidacy for violating an AU norm that discourages regional heavyweights from nominating their nationals for the union’s leadership positions.

Ruto’s approach to representing Africa’s positions in international forums, including his tendency to equivocate responsibility for the climate crisis by disavowing a supposed narrative of African victimhood, has been criticized by civil society groups and even some governments on the continent. His statement at the Africa Climate Summit that “we don’t want the North to pay, we all want to pay” landed poorly in African capitals and among climate justice activists, who advocate for a just energy transition for Africa that is mindful of its economic profile, the continent’s low contribution to the climate emergency as well as its disproportionate effect on African countries.

Ruto frequently positions Kenya as a climate leader in Africa that possesses an innovative energy mix that can attract foreign investment and which the rest of the continent can emulate. But Kenya's embrace of renewables and international carbon trading as a mechanism for climate cooperation is not widely shared across Africa, and Ruto has been criticized for using his position as CAHOSCC chair to narrowly shape Africa’s climate agenda in line with Kenya’s preferences.

The U.S.-based multinational consulting firm McKinsey played a major role in crafting the agenda at the Africa Climate Summit, which Kenya and the AU—which co-hosted the gathering—framed as an African-led opportunity to create solutions for the continent's climate transition. A network of 500 civil society groups from across the continent criticized the summit’s Nairobi Declaration as well as its adoption of carbon markets, carbon credits and embrace of costly technology as an alternative to phasing out fossil fuels. Their critiques were well-grounded, given that these prescriptions are shortcuts that enable rich, industrialized states to kick the can down the road using a smokescreen of carbon markets, geoengineering and other gimmicks. On climate change and other relevant issues, Nairobi’s tendency to adopt positions which contravene popular sentiment on the continent will not help Ruto’s ambition to raise his profile as a thought leader and position Kenya as a regional anchor.

It is reasonable for Nairobi to pursue a range of international partnerships that it believes would advance its interests and benefit its people. At the same time, Kenya’s ambition must be balanced by carefully designed aims and objectives that reconcile ends with means.

Having been in office for a little more than 24 months, Ruto has made no fewer than 66 foreign trips to nearly 40 countries—a rough average of three trips per month. He has argued that international travel is important to secure the foreign investments which Kenya needs to industrialize its economy, reduce poverty and enhance its position as East Africa’s anchor. His administration signed labor migration agreements with countries like Germany, the UAE and Qatar that he described as a means of tackling Kenya’s unemployment rate and boosting its inflow of remittances, but that is not a long-term solution to the country’s economic challenges.

The prevailing evidence does not support Ruto's claim that his frequent travels and diplomatic maneuvering tangibly benefits Kenyans. The less than impressive returns Kenya has accrued on its investment in a higher international profile points to a triumph of style over substance, as well as the ineffectiveness of a strategy that lacks acumen and farsightedness. That would likely hinder Nairobi’s ability to play the leadership role its leaders desire and stifle Kenya’s ability to win useful extractions out of the major powers amid the emergence of an order that it sees as favorable for its strategic interests.

Although the region gets far less attention in the discourse of Françafrique compared to West and Central Africa, France has former possessions and colonies in East Africa and the Indian Ocean like Madagascar, Mauritius, Djibouti, Mayotte, Réunion, Comoros and Seychelles.

As a "poor widow," (really), I can't contribute financially. However, Mr. Ogunmodede's essay would be a good base for a role-playing game by students in an African governance class. If such an event happened, it would be a loud, vigorous, and very useful for students to understand events by enacting them. Very fine essay. Sorry Mr. Ruto's method of administration involves so much travel. If he were a Senegalese wife her husband would divorce her.