How should Africa prepare for Trump 2.0?

African governments cannot afford to be idealistic in their engagement with Washington during Trump's second presidency.

“What does this mean for Africa?”

“Do you think Trump will visit Africa when he comes back?”

“Will he deport Africans living in America and ban us from coming there?”

“Chris, Trump moo jël election yi. c’est fou!” [A codemixed Wolof-French sentence that roughly translates to ‘Chris, Trump won the election. It’s incredible!’]

Questions and comments about what Donald Trump’s election to a second term portends for relations between Africa and the United States hit my WhatsApp faster than the ballot counting in Arizona’s Maricopa County. Many of the reactions came from Africans in different parts of the continent as well as others in the diaspora who evidently wanted to know what the outcome would mean for Africa’s engagement with Washington.

My view is in line with the broad consensus that Africa will not be a priority under Trump’s second administration. Because the “America First” ethos that was the guide star of foreign policy during Trump’s first term will endure, the continent would likely experience the same distrust, hostility and antagonism under Trump 2.0 that it did during his first administration.

This does not mean that Africans cannot and should not engage with the U.S. for the next four years — they don’t have much of a choice in any case — but the continent must be clear-eyed and sober-minded about the risks and opportunities that lie ahead and position itself to be able to respond effectively to them.

African leaders react to Trump’s win

African leaders were quick to join their global peers in congratulating Trump on his victory. A collection of the continent’s heads of state and government, from Nigeria’s Bola Tinubu and Zimbabwe’s Emmerson Mnangagwa to Djibouti’s Ismail Omar Guelleh and Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, sent their well-wishes and expressed their desire for close cooperation with his incoming administration.

The response of some African leaders to Trump’s win stood out over others. Take the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Morocco, South Africa and Uganda, which have seen their relations with the U.S. have taken different turns in the past few years and whose leaders all publicly congratulated Trump.

Morocco, Congo and Kenya have grown closer to Washington while U.S. officials regard Egypt, Ethiopia and Uganda to be problematic partners who must nonetheless be kept onside to prevent them from “flipping” to Washington’s geopolitical rivals. Gabon is something of a wildcard given its broad ties with a range of non-Western partners like Morocco and China and the relative newness of the regime of Gen. Brice Oligui Nguema, who deposed longtime President Ali Bongo Ondimba last year in a military coup. As for South Africa, it is arguably the sharpest African thorn in Washington’s side given its spats with the U.S. on issues linked to Russia’s war in Ukraine and the genocide case it is pursuing against Israel at the International Court of Justice.

The leaders of these countries sought in their congratulatory messages to appeal to Trump’s well-known appreciation for flattery. Kenya’s William Ruto and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa were said to have held phone calls with the U.S. president-elect. As commentators assess what Trump’s return to the White House would mean for U.S policy in Africa, the word “transactional” has been mentioned ad nauseum given his proclivity for personalist governance and the wheel-and-deal games that were common in his first term. Many African leaders and senior officials likely welcomed Trump’s return to the White House based on a belief that it would mean a reduced U.S. emphasis on matters like human rights, anti-corruption and LGBTQ issues.

This assumption might explain why the speaker of Uganda’s parliament reportedly said that sanctions imposed on her by the Biden administration were “gone” after Trump’s win. The spokesperson of South Africa’s foreign ministry stated in a now-deleted post on X that “historically, relations between South Africa and the US thrive under a Republican White House.” Other African leaders and top officials appreciate what they see as Trump’s directness and preference for “deals” over trite lectures about democracy and “good governance” that they are accustomed to hearing from U.S. officials.

Notwithstanding many areas of disagreement with Washington that are certain to emerge under Trump 2.0, some African policymakers believe that his desire to counter China’s influence in Africa could unlock collaborations with the U.S. that would stimulate economic growth, reduce poverty and spur innovation on the continent. This assumption is overly optimistic given Washington’s track record but it is a commonly held belief in African capitals.

One possible tendency to look out for in a second Trump administration is the dispatching to Washington and Mar-a-Lago of “whisperers” like Franck Biya, Seyi Tinubu, Johann Rupert, Raph Kabengele, David Lagat and other notable figures with close personal ties to the continent’s leaders. In addition to the usual array of DC-based lobbyists who broker engagements between Washington and African governments, these individuals — many of whom do not hold official government positions — can be expected to make major waves with a U.S. administration which is equally likely to look outside the foreign-policy bureaucracy to sanction diplomacy.

Trump’s popularity in Africa is overstated …

Since Trump’s emergence in the 2010s as a prominent political figure, he has gained a significant following among Africans.

On Facebook, WhatsApp, X and other digital spaces used heavily by Africans, pro-Trump content and commentary was constant during the three presidential elections in which he ran as a candidate. His two victories in 2016 and 2024 inspired prayer points among many African churchgoers, particularly those who belong to the Pentecostal denominations that are the fastest-growing segment of Christianity on the continent. It is common to see images of Trump across the continent in paintings, on decals and other decorations.

Support for Trump in Africa has often confounded international media, given his well-documented hostility to African nations that included a reference to “shithole countries” and travel bans his administration imposed on several of them during his first term. The Economist ran an article in 2018 titled ‘Why Donald Trump is Popular in Africa.’ The following year, The Africa Report wrote that “Africa gives a thumbs up to Donald Trump’s America.” CNN’s Larry Madowo penned an article about Africans who rooted for Trump to win the 2024 presidential race and shared it on X with a caption that read “This is why Trump remains popular in Africa though the US isn’t.” It wasn't completely clear what he meant by “this” although he might have been alluding to the arguments he made in the piece.

The U.K.’s Channel 4 and Germany’s Deutsche Welle have run segments exploring Trump’s popularity among Nigerians, while The Guardian and African Arguments published articles trying to make sense of why many of them gravitated toward Trump. In 2020, I was interviewed by GZERO Media, a subsidiary of the Eurasia Group, about perceptions in Nigeria about that year’s U.S. presidential election and discussed local impressions of Trump, among other topics. The discussion covers much of what I have previously written about in these pages and you can check it out here.

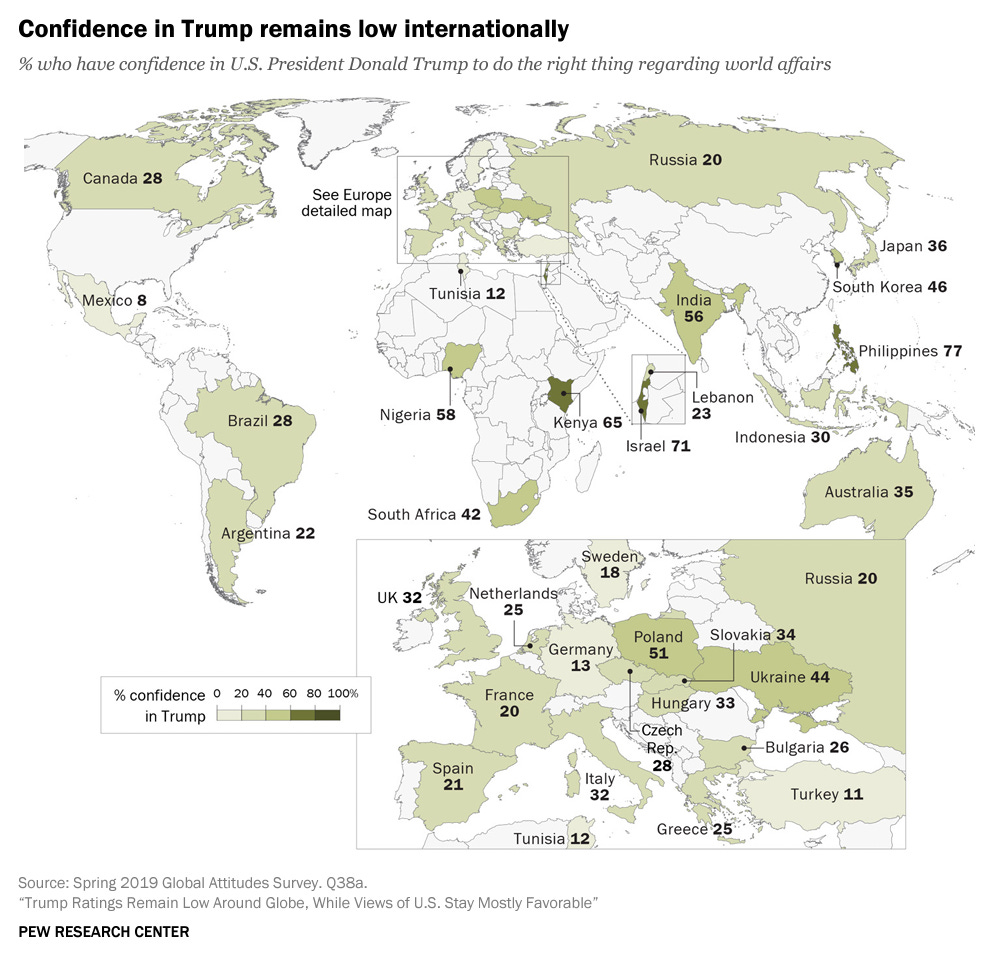

Few extensive attempts to measure Trump’s reported popularity in Africa have been made. During his first term, foreign commentators who advanced the claim of Trump’s popularity in Africa tended to point to three main sources. The first was the above-mentioned Economist piece from 2018. The second was a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center in which Nigerians and Kenyans—who were among the survey’s respondents from four African countries—expressed trust in Trump’s judgment on foreign affairs. The third data point was Gallup’s 2020 Rating World Leaders survey which polled respondents in 38 African countries about “U.S. leadership.” The survey found that median approval among Africans of U.S. leadership in global affairs stood at 52%, with majorities in 21 of the 38 African countries surveyed registering a positive sentiment of the U.S.

When examined more critically, however, the claim of Trump’s popularity on the African continent is exaggerated. It leans heavily on examples from Nigeria and Kenya, two former British colonies with a large number of evangelical Christians and an entrenched pro-West sentiment among their populations.

Depending on how one defines “Trump’s popularity,” none of the data points mentioned above measured Trump’s individual approval rating. Instead, they used his policies or the United States as proxies for sentiment about Trump. It is conceivable and perhaps even likely that many Africans who trust Trump’s judgment on foreign affairs and approve of his policies also like him personally, but that is not a given.

The Pew survey findings are not representative of the entire African continent, given that they surveyed opinions from only four countries, three of which are English-speaking nations—Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa—of a broadly similar macroeconomic profile. As for the Gallup survey, its authors pointed out that the image of the U.S. has always been the strongest of any geographic region regardless of who the U.S. president is.

As I have noted previously, Africans have consistently held a positive image of the U.S. that is generally independent of their views of its domestic affairs, political leadership and foreign policies. It might be the case that Trump is genuinely popular on the African continent, but that is a claim that has yet to be robustly tested let alone demonstrated.

… but it is real and requires nuance to understand and appreciate

None of this dismisses the idea that pro-Trump sentiment does exist among Africans and is worth interrogating. For instance, Trump and other Republican politicians—who tend to be anti-abortion, oppose LGBTQ rights and hold right-wing positions on “family values” issues—find significant approval on a continent where religiously devout people with conservative views on social issues are the norm.

Similarly, in countries where their governments have gotten into disputes with Democratic administrations—usually over domestic politics and regional conflicts—it is common for domestic supporters of that administration to back Trump based on a belief that he would reverse Washington’s stance on said issues. By the same token, the support of a Democratic administration for a government’s policies often triggers pro-Trump sentiment among many of its local critics.

For many of Trump’s African admirers, his wealth and celebrity, rhetorical bluster and disregard for institutional norms that he believes are an obstacle to achieving his policy goals all ring familiar to people on a continent where extreme poverty remains commonplace and authoritarian rule is prevalent. The tired, racist “jokes” about Trump acting like an African dictator might have been overwrought and ignorant of the United States’ own history of authoritarianism, but the archetype he projected was one many Africans recognized from their own contexts.

Pro-Trump sentiment in Africa is also more broad-based than commonly believed. Trump draws admiration from a crosscutting fragment on the continent that includes pro-West urban professionals, avowed anti-imperialists and traditionalist reactionaries. The common denominator of this seemingly incompatible group is its shared commitment to an accelerationism toward outcomes that they desire and believe Trump can help realize. Precisely because of Trump’s hostility to Africa and his atavistic view of foreign relations, these people support his agenda because they believe that his lack of interest in Africa and the cruelty of his policies would equal a total neglect of the continent that would drive African governments toward self-reliance.

To cite one example, Trump’s admirers on the continent tend to believe that U.S. and Western aid is bad for Africa. Their reasons vary, running the gamut from a conviction that it fuels corruption and creates a culture of dependency on the West to a belief that aid is a mechanism of neocolonialism and part of a conspiracy to keep Africa poor. These pro-Trump segments are united by an earnest belief that ending Western aid to Africa would compel the continent’s leaders to “solve their own problems.” In their view, Trump’s isolationism which materializes in immigration restrictionism, his lack of interest in democracy promotion and distaste for foreign commitments would break Africa’s reliance on the West that they believe has prevented the continent and its people from taking full responsibility for their own fate.

Although these arguments appear on the surface to be empowering, they are naïve and myopic, by misunderstanding the drivers of Trump’s conservative nationalism; handwaving the second- and third-order consequences of Trump’s policies; and failing to grapple with the ways in which Trump’s lack of interest in and hostility to Africa created bad incentives vis a vis Washington’s engagement with African states during his first term. For instance, Trump’s transactionalism drove his administration’s decision to sell warplanes to Nigeria, an expenditure then-President Muhammadu Buhari paid for with funds from the country’s Excess Crude Account that were withdrawn without the approval of the legislature. When Nigerian soldiers killed Shia protesters in 2018, the army cited Trump’s words to justify their actions. Realpolitik considerations of great-power competition with China informed the Trump administration’s decision to embrace the result of a rigged vote in Congo and Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara’s controversial election to a third term in 2020.

Washington generally looked the other way from corruption and human rights abuses committed by its partners in countries like Egypt, Morocco, Niger, Ghana, Kenya and Uganda during Trump 1.0. Despite Trump’s rhetoric, his administration lent support to repressive regimes on the continent much like his predecessors did. His administration saw a sharp drop in U.S. refugee admissions—it resettled more than 57,000 people from Africa—and in October 2020, Trump signed a directive capping the number of resettlements at the lowest figure since the establishment of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program in 1980. Contracts negotiated between the Trump administration and vaccine manufacturers at the early onset of the COVID-19 pandemic prohibited the U.S. from sharing surplus doses with the rest of the world, and set the stage for the “vaccine apartheid” that crippled the vaccination effort of developing countries in Africa and elsewhere.

The belief among some Africans that Trump’s transactionalism and unconcealed callousness is preferable to what they regard as the insincerity of the liberals who make up Democratic administrations is steeped in a nihilism that masks itself as realism. It is not a plan for dealing with either the U.S. or the world at large as it exists, and at its worst will cause too many Africans to suffer unnecessarily. But those who support this worldview just might get the opportunity to see their ideas put to the test.

Might Trump spring a pleasant surprise in U.S.-Africa relations?

Days before the 2024 U.S. presidential election, Semafor ran a piece about what it termed the “pragmatic turn” of Trump’s “Africa plans.” After the vote, openDemocracy published an article by an author who argued that Trump’s “pragmatic, investment-centred vision isn’t entirely bad news for the African continent.” Another piece in The Africa Report declared that “ignoring Africa’s potential would be a significant missed opportunity” for a second Trump administration. These takes cohere with the cautious optimism with which many African leaders and government officials received the news of Trump’s election to a second term. Some commentators echoed the sentiment expressed by South Africa’s foreign ministry spokesperson that Republican administrations are better for Africa than their Democratic counterparts, while some more measured observers have expressed hope that Trump’s lack of interest in Africa might enable more creativity on the part of U.S. ambassadors on the continent.

Much like those who embrace Trump out of a misguided belief that weakening Washington’s ties to the continent would cause it to “leave Africa alone,” these glass-half-full attempts at “practicality” are based on wishful thinking and a selective interpretation of facts. To begin with, Trump’s foreign-policy Cabinet picks have no demonstrable record of engaging with the continent and are likely to outsource Africa policy to lower-level officials in order to focus on more urgent priorities like Europe, the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific. This will not bode well for hopes of the economic relationship between Washington and African countries that many claim to desire.

Leaving aside that Trump’s Africa policy was no more transactional than Biden's as well as that of his predecessors, the neoliberal “trade not aid” mantra many believe in is a false dichotomy that does not exist in the real world. I take a back seat to few people in my critique of the aid industrial complex, but aid was always intended by its originators to complement private sector development. The state formation, market development and absorptive capacity that low-income countries must achieve in order to make trade and commerce productive will not magically appear from thin air, and typically requires aid assistance to consolidate. Warts and all, aid programs in health, education, nutrition, energy and other sectors are vital for millions of Africans and calls for their reduction or elimination must come with a backup plan.

The hope that Trump 2.0 would pursue a partnership with Africa built on trade, investment and entrepreneurship requires a suspension of disbelief. Trade between the U.S. and African countries is on the decline, as it has been for many years. The first Trump administration scarcely demonstrated interest in expanding the United States’ commercial footprint on the continent. If anything, Trump imposed tariffs on Rwanda after a dispute over textile imports and expressed opposition to a renewal of the African Growth and Opportunity Act. His administration’s pursuit of a bilateral free trade agreement with Kenya went against a consensus on the continent that economic agreements with African countries ought to be coordinated by regional economic organizations and uphold the African Continental Free Trade Agreement’s integrationist objectives. Although many credit Trump for overseeing the creation of Prosper Africa and the Development Finance Corporation, two measures praised by U.S.-based “Africanists” and which Biden retained support for, their tangible impact to date is negligible.

Trump’s return to power could stall progress on Africa’s key global priorities like silencing the guns, a just climate transition and overhaul of the global financial architecture. His administration would likely oppose the continent’s proposals to reform the United Nations (UN) and other international organizations, and is certain to cut funding to global institutions and programs which African states depend heavily on. During his first term, Trump’s disdain for the global multilateral system created by the U.S. and its allies after World War II had major consequence on the continent. Nowhere was this effect more visible than within the UN system.

The U.S. is the single-largest donor to the UN, having contributed nearly $18 billion — a third of the funding for the body’s collective budget — in 2022. Although the number of UN peacekeepers deployed to African countries is on the decline, the continent has been home to more than 30 UN peacekeeping missions since 1960 — the most of any geographic region — including some of its largest missions in countries like Mali, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Central African Republic. During Trump’s first administration, delays and cuts to Washington’s contributions to the UN’s peacekeeping budget1 adversely affected the effectiveness of UN missions in African countries and likely had a negative impact on the broader peace and security atmosphere there.

Similarly, Trump’s suspension of payments to the UN Population Fund, cuts to funding for the UN Program on HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO)2 hampered the financial and technical support these agencies provide to African partners who implement crucial programs that save lives and help improve other outcomes. Trump’s withdrawal of the U.S. from the UN Human Rights Council, Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement as well as its attempt to pull out from the WHO all signaled to African governments a capriciousness about a set of institutions that Washington played a leading role in creating and which they have relied on for decades.

Trump’s second administration will overlook the transgressions of Washington’s African partners as well as those it is courting and penalize those who run afoul of the U.S. including by tilting too far in Moscow’s or Beijing’s direction. The Lobito Corridor project launched by the Biden administration would likely appeal to Trump’s desire to “compete” with China and it is possible he expands it or creates similar initiatives elsewhere on the continent amid Washington’s race to secure “critical minerals” needed for the global transition to clean energy. Rebels like South Africa, Algeria, Ethiopia and the members of the Alliance of Sahel States—Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger—might incur more of Washington’s wrath and be brought to book for not towing its line on important issues.

Trump is almost certain to reinstate many if not all of the policies he implemented in his first term that were reversed by his successor, Joe Biden. His administration will provide weapons, funding and training to partner countries like Kenya—which Biden designated as a major non-NATO ally of the U.S.—whose security forces will likely use that assistance to kill, torture and repress their fellow citizens. His plan for a mass deportation of undocumented migrants and pledge to impose tariffs on imports to the U.S. would likely negatively affect Africa by slowing down remittances to the continent, causing trade disruptions that would create headwinds in African countries and triggering an economic contraction that could become global in scope. Amid intensifying debt crises in many parts of the continent, his administration might weaponize the structural advantages Washington has in the World Bank and IMF.

Trump is notoriously difficult to predict, and no one can see the future. His administration could turn out to achieve more meaningful things in its relations with African countries than expected. The U.S. Congress might play a more significant role on Africa policy and hold off on some of Trump’s more sweeping proposals like drastic cuts to U.S. aid, much like it did during his first term. Despite Trump’s mercurial nature and hostility to Africa, the continent’s leaders must engage with Washington for the simple reason that it is too important an actor to ignore. At the same time, they need to be more serious-minded about their diplomacy and set clear, time-bound objectives regarding their priorities.

Going forward, African states must be less short-termist in their thinking and pursue a multidimensional foreign policy that leverages the range of partnerships they are developing across the world. None of that would guarantee that dealing with the Trump administration will come easy; afterall, African states are not the only actors with agency. What is certain, though, is that they must plan for engaging the world’s lone superpower and prepare for uncomfortable circumstances that they might soon find themselves ensnared in.

During his first term, Trump opposed the U.S.’s 28% assessed contribution to the UN peacekeeping budget and negotiated with the U.S. Congress to lower it to 25%. Biden maintained that cap.

In 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump administration announced that the U.S. would withdraw from the WHO completely and cut funding further. Joe Biden halted the planned U.S. exit from the WHO and resumed funding for the agencies that saw cuts under Trump.

I agree but in a broader sense suspect that you may be off because the ultimate effects of the worst case scenario may be very beneficial for most countries and most people within most countries in Africa.

The planetary unified economic regime that seemingly all of Africa is for the most part locked into suppresses development.

But America was protectionist during its entire development phase. Also, its was internally trade illiberal, it had interstate/local protectionism and semi-fragmented internal capital markets. China from the 1980s until now (or at least recently, Xi et al. have been trying to change this) also had protectionism outwardly, and also had internal local trade protectionism and semi-fragmented capital markets

A big example (just one of several!), and one that is very relevant to the current talk among some that Africa should have a common currency, is that the US did not get an internal common currency until also 150 years after its creation, while the Constitution gave the power to coin money and regulate its value in 1789, it is still the case that a common currency within the USA didnt come for much longer. For most of the 19th century, the U.S. had a decentralized system where individual banks issued their own banknotes (once developed, we had thousand of currencies!), then the National Banking Acts (1863–64) significantly lessened them (largely through a t10% tax on them, but the NB’s currencies were also to an extent diff currencies) and then the Federal Reserve system in 1913 soon brought in a uniform national currency