25 developments that have shaped Africa's 21st century

A review of significant trends in African politics, economics, culture, demographics and foreign affairs from 2000 to 2025.

Happy new year friends. I hope that the Christmas holidays were kind to you and your loved ones, and I wish you a blessed year ahead.

Thank you for your readership and engagement in 2025. I will do my best this year to continue my mission of offering insights about events and developments taking place on the African continent and laying out informed, perceptive ways of thinking about them.

Last week marked the conclusion of the first quarter of the 21st century, one that many referred to as an “African century.” The phrase is strongly linked to the Pan-Africanist concept of the “African Renaissance,” and gained currency in the 1990s due to its use by prominent figures such as Nelson Mandela, Olusegun Obasanjo, Kofi Annan and Thabo Mbeki, who is often credited with popularizing the phrase.

By 2000, the beginning of the fifth decade since African states began to win formal independence from European imperial powers, multiparty democracy had replaced colonialism, white-minority rule and military and single-party dictatorships across the continent.

Several of the internal conflicts and civil wars that had claimed many lives—such as in Burundi, Rwanda, Mozambique, Liberia and Sierra Leone—had either ended or were on the wane.

African economies had started to turn the corner by the late 1990s after the retrogression of the so-called SAP years, when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank imposed structural adjustment programs on African societies in response to rising debt and other economic crises.

That progress looked to have consolidated by the mid-2000s, when the idea of an “Africa Rising” entered popular lexicon as a way to describe the optimism that characterized Africa’s outlook in the 21st century, especially with regard to the economic prosperity, political stability and strategic autonomy that the continent’s people have long desired.

This post reviews Africa’s journey through the first quarter of the 21st century (2000 to 2025) by drawing out 25 key trends and developments that have shaped the continent’s trajectory and will likely continue to do so for the foreseeable future. I have divided them into five categories: culture, demographics, economics, international affairs and politics.

CULTURE

I. Globalization has led to a blending of traditional African elements with global trends, creating hybrid cultural expressions such as the fusion of African dishes with modern cooking techniques or the semi-formalization of mixed languages like Nigerian Pidgin, Nouchi in Cote d’Ivoire, Sheng in Kenya and the creoles and “girias” spoken in former Portuguese colonies such as Angola, Cabo Verde, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique.

A significant concern is the erosion of African customs and languages due to urbanization, the dominance of Western education and media as well as the widespread use of English and other European languages.

II. There is an increasing desire and effort by younger generations of Africans to reconnect with and reembrace “indigenous” languages, naming traditions and religions and spiritualities. This marks a considerable shift from previous generations which shied away from such practices due to factors such as globalization and the legacy of colonialism. Equally, many Africans are using digital technologies to preserve African histories, languages, traditions and knowledge systems.

III. Media pluralism and the digital revolution have amplified African voices globally by creating spaces for them to tell their stories, challenge stereotypes, connect with global audiences and define what it means to be African in the 21st century, fostering new forms of sociocultural exchanges.

IV. Rapid urbanization is congruent with—and in some cases, causing—a normative evolution of beliefs and practices such as cohabitation, a shift from communal to more individualistic lifestyles and the “nutrition transition” from traditional diets rich in fiber and carbohydrates towards processed meals and other Western-oriented diets that are high in sugar and saturated fats. Awareness about practices that are regarded as harmful to women and children is increasing alongside efforts to eradicate them, with varying outcomes across the continent.

V. African contributions in art, music, fashion, film, literature and sport have gained global prominence and are driving significant growth in domestic creative industries. However, key obstacles remain around infrastructure, intellectual property, talent development and other shortcomings.

African music genres such as Afrobeats, amapiano, bongo flava, coupé-décalé, ndombolo and other styles that blend traditional sounds with modern influences are popular across the globe. Music artists like Ayra Starr, Burna Boy, Davido, Diamond Platnumz, Fally Ipupa, Kabza De Small and Tems are globally recognized acts who showcase Africa’s rich musical landscape.

Contemporary fashion designers have gained international acclaim by incorporating traditional artisanal techniques and textiles like àdìrẹ, bogolan, kente and shuka into stylings that are adaptable to multiple occasions. These trends are popular on the continent and have been adopted by the African diaspora and beyond it, thereby promoting sustainable fashion and local craftmanship.

A growing international appetite for diverse voices, fueled by increased African visibility, is expanding the readership of African literature. Genre diversification and an increase in published works by writers from less-represented African nations has enriched the literary landscape.

A wave of independent publishers that includes Cassava Republic, Éditions Jimsaan, Modjaji Books, Jahazi Press and Huza Press has emerged, while a range of online platforms and resources that includes Afrireads, Brittle Paper and Chimurenga cater to local readers, spotlight emerging writers and invest effort in translating and publishing works from and to African languages.

African cinema and visual arts are characterized by the increasing use of diverse media to explore new forms of expression, center African experiences and engage with contemporary issues such as globalization, poor governance, migration and the legacies of colonialism. New festivals showcasing the continent’s creativity have emerged like the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, ART X Lagos, Africa International Film Festival and Chale Wote.

Sports in Africa have been transformed by the professionalization of talent, increased investment, digital adoption and the rise of women’s sports. African athletes like Achraf Hakimi, Eliud Kipchoge, Faith Kipyegon, Kenenisa Bekele and Samuel Eto’o have become world beaters in their respective sports, while there is an increased emphasis on developing local talent and sports ecosystems through community programs and improved governance.

I know how much my subscribers and other readers have enjoyed the music playlists I have shared in the past. Because I am a nice guy, I crafted not one but two 100-song playlists with some of my favorite African music records from the 21st century. You're welcome.

One is a strictly Nigerian playlist of songs that are commonly grouped under the imprecise label of “Afrobeats” while the other is a more pan-continental collection of records. The two mixes are an entirely subjective selection, and I had only two rules when selecting the records: The songs must have had cultural resonance in African countries and across the continent, and I selected no more than three songs from one artist. I hope you enjoy listening to the playlists as much as I loved curating them.

DEMOGRAPHICS AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

VI. Africa’s foremost demographic trend is a rapid population growth that has created the world’s youngest and fastest-growing populace, marking a significant shift with global implications.

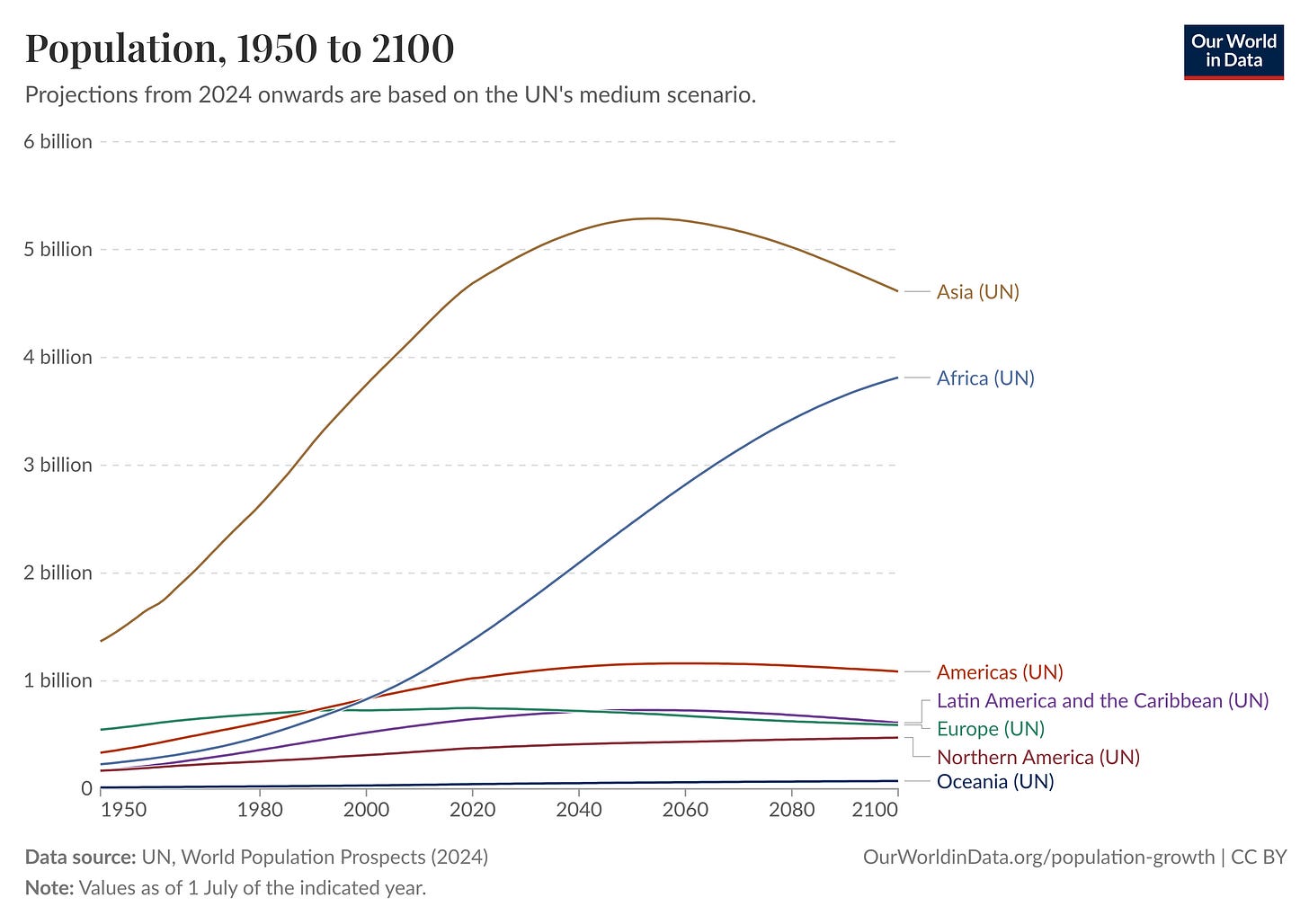

Africa’s population expanded from approximately 831 million in 2000 to more than 1.5 billion in 2025, and has been projected by the United Nations (UN) to reach 2.5 billion by 2050 and potentially 4 billion by 2100.

Africa’s share of the world’s population is rapidly increasing. It is projected to reach 28% by 2050 and potentially 40% by 2100.

VII. Africa’s expanding population has significantly altered the global religious landscape. Christianity and Islam—the world’s two largest religions by number of followers—are growing in Africa, driven by trends such as the rise of Pentecostal and charismatic movements, the “pentecostalization” of mainline Christian denominations, the popularity of African Islamic orders and the complex interplay of African spiritualities and the two Abrahamic religions. African diasporas in Europe and North America, two regions with high rates of secularization, are revitalizing Christianity.

VIII. Africa is experiencing the world’s fastest urbanization rate, driven by factors such as rural-urban migration, economic expansion and higher education attainment rates.

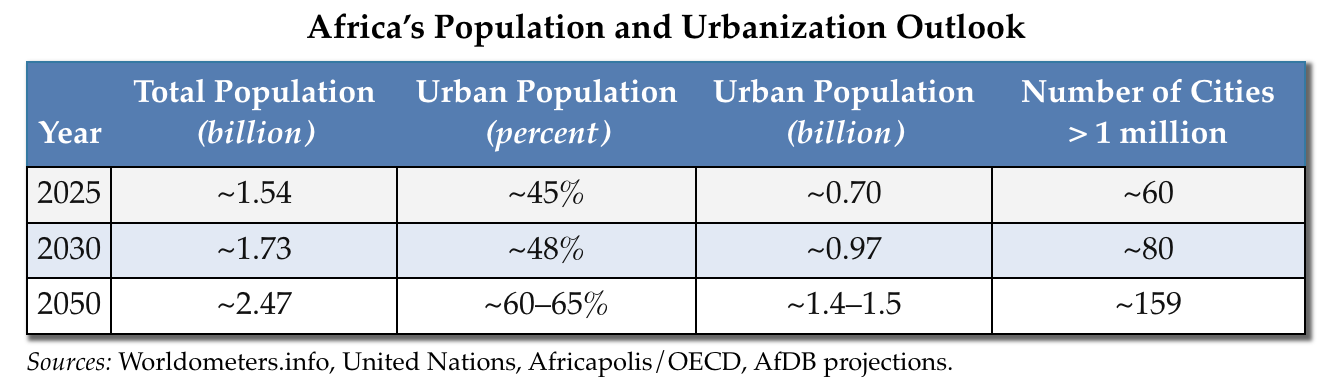

The continent’s urban population increased from 31% in 1990 to 44% in 2023 according to ISS African Futures, and some estimates expect it to reach 60% by 2050.

Megacities like Cairo, Kinshasa and Lagos are at the forefront of this growth, while other large cities like Abidjan, Addis Ababa, Dar es Salaam, Dakar, Johannesburg, Luanda and Nairobi are expected to become megacities by 2050. Lagos is projected to become the world’s most populous city by 2100.

The AU said that Africa’s urban population is expected to double by 2050 with cities expected to absorb an additional 600 million people, bringing Africa's urban population to 1.2 billion. Cities are projected to absorb up to 80% of Africa’s population growth and it is estimated that two in three Africans will live in urban areas by 2050.

The number of cities with more than 1 million people is increasing, with projections that the number of such cities will reach 159 by 2050.

IX. The continent’s median age of 19 signifies its youth, with children and young adults between the ages of 18 and 35 making up a large majority of the population.

The world’s 10 youngest countries are all in Africa.

Infant and child mortality rates have drastically shrunk, while life expectancy has improved but is still significantly lower than in other parts of the world.

Fertility rates in Africa are declining from their peaks of previous decades but remain significantly higher than the global average, leading to population momentum on the continent.

Deaths from communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional causes declined by more than 30% from 2000 to 2020 reflecting progress in expanding immunization, improved child survival and better access to basic health interventions.

X. Africa’s rapid, unprecedented population growth creates the potential for a “demographic dividend” but also intensifies the demand for jobs, education and infrastructure as the continent's large youth cohort transitions into working age and its elderly population grows. A large, young workforce can drive economic growth and innovation if provided with skills, health and opportunities but can present societal problems if its needs and expectations are unmet.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

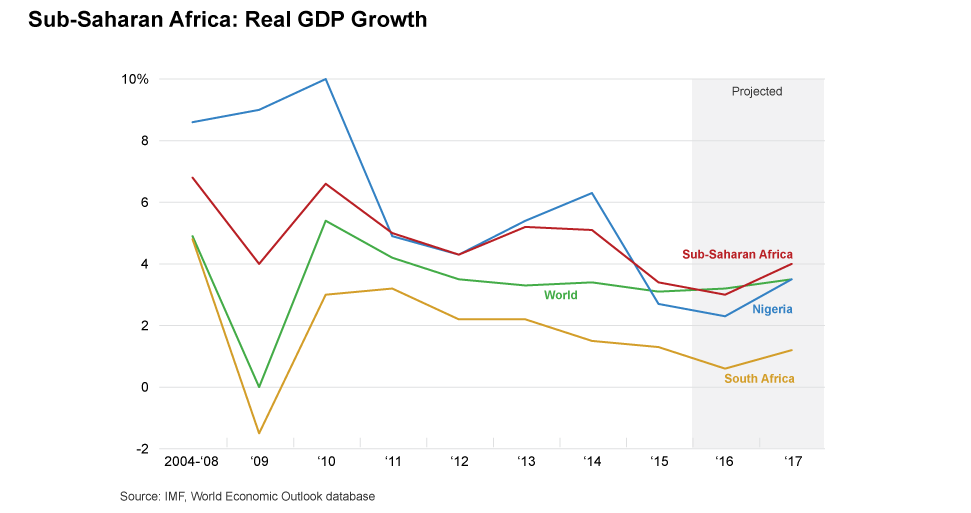

XI. African economies have experienced significant expansion since 2000 driven by factors such as improved governance and stability, increased trade with rising economies like China, a surge of foreign investment inflows, infrastructural development, the digital revolution and a youthful, enlarging workforce.

According to UNCTAD, Africa grew by 4.8% annually from 2000 to 2010, outpacing the global average of 3.1%. Africa’s growth slowed to 3.1% between 2011 and 2020 but remained above the global average of 2.4%. This expansion was strongly linked to commodity price booms and the growth of services such as banking, construction, retail and telecommunications.

However, structural transformation has been uneven while per capita income growth has been modest. Ongoing policy challenges include the gap in per capita income between African nations and industrialized economies; rising poverty levels; pressures from urbanization, climate change and other external shocks; a major push towards regional integration; and continuing efforts to diversify from commodities, subsistence agriculture and “informality.”

XII. Africa’s economic titans have slacked, smaller nations have punched above their weight and unlikely star performers have emerged.

The continent’s economic heavyweights—specifically South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and Angola—have been sluggish in recent years and constricted growth within their respective regions. However, Ethiopia has been one of the continent’s largest and fastest-growing economies, achieving average annual growth rates of more than 10% for most of the 2000s and 2010s.

In recent times, the likes of Bénin, Guinea, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal and Togo have regularly been listed among the fastest-growing economies in the world while second-tier economic hubs such as Botswana, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Namibia and Tanzania have often backstopped macroeconomic stability in their regions when their larger, wealthier neighbors have experienced volatility.

XIII. Africa’s mobile revolution has transformed African economies and societies by increasing rates of internet and mobile penetration, boosting financial inclusion, stimulating economic empowerment especially in sectors like agriculture and retail, fostering public awareness via civic technology and shifting modes of social engagement.

The mobile boom, which was enabled by the liberalization of telecommunications sectors across the continent from the 1990s onwards, took off when corporate giants such as MTN, Orange, Airtel, Econet, Vodacom and Africell entered African markets for the first time or expanded their existing footprint within them.

According to the GSM Association (GSMA), a consortium of global mobile phone operators, there were 710 million unique mobile subscribers in Africa in 2024 and mobile technologies and services generated nearly 8% of GDP across the continent, a contribution that amounted to $220 billion of economic value added.

Mobile money systems such as m-pesa in East Africa and Orange Money in West Africa have made mobile banking and payment systems accessible to millions of previously unbanked people, while platforms like mPedigree provide SMS-based authentication services used to verify prescribed medications and fight counterfeit drugs in countries like Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.

Modern technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things and robotics are presenting both opportunities for economic transformation and challenges related to capacity, infrastructure and ethics.

XIV. Several statistics including from the World Bank have suggested that the number of people in “Sub-Saharan Africa”1 who live in extreme poverty reduced from nearly 60% of the population in 1993 to 35% in 2019.

However, the pace of poverty reduction decelerated during the 2010s due to economic slowdown in many African countries. Rapid population growth and the COVID-19 pandemic have led to a new increase in both the number and share of Africans living in poverty.

Africa has the highest rate of extreme poverty in the world, with 32 African nations making up the 44 listed by the UN as Least Developed Countries (LDC). Nigeria’s poverty rate has spiked in the past decade, and the World Bank projected last year that Nigeria’s poverty rate would reach 62% in 2026—approximately 141 million people.

XV. African economies remain susceptible to several vulnerabilities that underscore the need to boost their economic resilience.

African economies continue to be heavily reliant on the export of raw materials. UNCTAD asserted in 2024 that more than half of African nations depend on oil, gas and other minerals for at least 60% of their export earnings, leaving them vulnerable to volatile global markets.

Global crises such as the 2008 financial crisis, the so-called Arab Spring, the mid-2010s commodity crash, COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine highlighted these vulnerabilities, all of which amplify Africa’s structural weaknesses and hinder its ability to drive long-term development.

Debt crises have resurfaced across the continent years after the so-called debt forgiveness of the mid-2000s.

Multiple countries such as Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Ghana and Kenya currently have an active IMF program.

Several sources including the IMF and World Bank have stated that the median debt-to-GDP ratio in African economies has reached 60%, the commonly referenced benchmark for public debt limits.

External borrowing from China as well as private creditors including commercial banks and Eurobonds have significantly altered the continent’s debt profile in comparison to the 20th century.

Climate change and energy poverty have compounded the continent’s sustainable development challenge.

The African Development Bank has stated that more than 600 million Africans do not have reliable access to electricity, representing about 83% of the global energy deficit.

A report by the World Meteorological Organization claimed that climate-related hazards are causing African nations to lose up to 5% of their GDP annually.

GEOPOLITICS, FOREIGN POLICY AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

XVI. The rise of African agency illustrates the continent’s inclination to become an autonomous, influential force in global politics, underscoring the desire by African people to reject framings of the continent as a passive recipient of external agendas and actively shape international affairs.

XVII. Since the turn of the century, Africans have stepped up their demand for reform of multilateral institutions, which is centered around getting equitable representation within those bodies, correcting historical injustices and ensuring that global governance reflects contemporary realities.

The Ezulwini Consensus is a foundational framework that established the AU’s collective position on reform of the UN Security Council (UNSC). Its main objective is to secure two permanent, veto-wielding seats for Africa on the UNSC. The AU established a Committee of Ten (C-10) Heads of State and Government to drive this agenda.

Africans have called for an overhaul of the global financial architecture, which includes proposals to restructure the G20, credit rating agencies and international financial institutions (IFIs) like the IMF and World Bank in order to ensure that they better reflect the continent’s needs.

African demands have focused on greater voting powers, debt relief, reallocating Special Drawing Rights, fairer financing for climate action and an end to policies that promote austerity.

In 2023, the G20 accepted the African Union’s bid to join the group and South Africa hosted its leaders’ summit last year, marking the first time that the event was held on African soil.

In recent years, African states and civil society groups have taken up climate justice as one of the continent’s international priorities in light of the disproportionate effects climate change has had on Africa despite the continent’s minimal contribution towards global greenhouse gases. Their demands typically include delivering on climate finance pledges made by industrialized nations to developing countries and framing technology transfer and loss-and-damage as a legal obligation to low-income nations instead of aid.

XVIII. African states are diversifying their security and economic partnerships beyond their traditional Western collaborators.

China and India have become two of Africa’s largest trading partners, and ties with Beijing have become the continent’s most important external relationship.

Russia remains a prominent—if overstated—actor in parts of Africa, while prominent “others” including Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia and the Gulf Arab states have emerged as key interlocutors of African states.

French influence in West Africa has taken a nosedive amid a backlash against French security policy in the region and a bourgeoning wave of sovereigntism that is strongly linked to opposition to françafrique, the neocolonial system of relations between Paris and its former colonies in Africa.

The slogan ‘trade not aid’ has emerged as a mantra for the desire by many Africans to shift relations with Western powers from a focus on development assistance towards fair trade and commercial partnerships.

Funding for foreign aid, which has declined significantly since the 1990s, saw a drastic reduction in 2025 due to cuts to U.S. foreign aid implemented by U.S. President Donald Trump. Many Africans have welcomed this shift in global development as a necessary step to reducing dependency on foreign donors and encouraging more African self-reliance.

XIX. There is an increased push for regional and continental integration that is rooted in a desire to achieve a united, prosperous Africa through economic cooperation and political unity.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) aims to create a single market of 1.5 billion people—the world’s largest free trade area—that its proponents say will increase African prosperity by easing the movement of goods, services and capital across the continent.

African states, the AU and regional bodies such as the Economic Community of West African States and the East African Community have implemented significant if uneven measures to boost intra-African travel.

African efforts at integration are concurrent with the AU’s principle of adopting a “common African position” on global issues that would position the continent to speak with one voice and strengthen its bargaining power in international negotiations.

XX. Pan-Africanism and connections between people on the continent and African diasporas are evolving, along with beliefs around hybridity, migration and identity.

African diasporas make up a growing portion of domestic economies through remittances, trade and investment.

The AU has included the African diaspora as its sixth region alongside North, South, Central, East and West Africa. Several West African nations like Bénin, Ghana, Sierra Leone and The Gambia have launched programs offering citizenship to foreign nationals who descend from people who were shipped from African shores and enslaved overseas.

Initiatives like Ghana’s “Year of Return” and Nigeria’s “Detty December” are aimed at attracting African diasporas to the contient.

Although many young Africans are either skeptical of Pan-Africanism’s suitability to modern times or believe it lacks a proper definition, their desire to build bridges with other Africans as well as people of African descent in global diasporas has not wavered.

The relative popularity of individuals like Captain Ibrahim Traoré, PLO Lumumba, Julius Malema and Wode Maya suggests that there is demand for a philosophy that is centered on the continent’s uplifting and liberation.

POLITICS, GOVERNANCE AND INSTITUTIONS

XXI. The transition towards multiparty democracy that began in the late 1980s has sustained itself, and a majority of Africa’s population lives in countries where political authority is nominally vested in elected civilians.

African states generally tend to be “hybrid regimes” that run the gamut from defective democracies characterized by competitive authoritarianism like Ghana, Kenya, Namibia and Senegal to electoral autocracies such as Egypt, Nigeria, Rwanda and Zimbabwe.

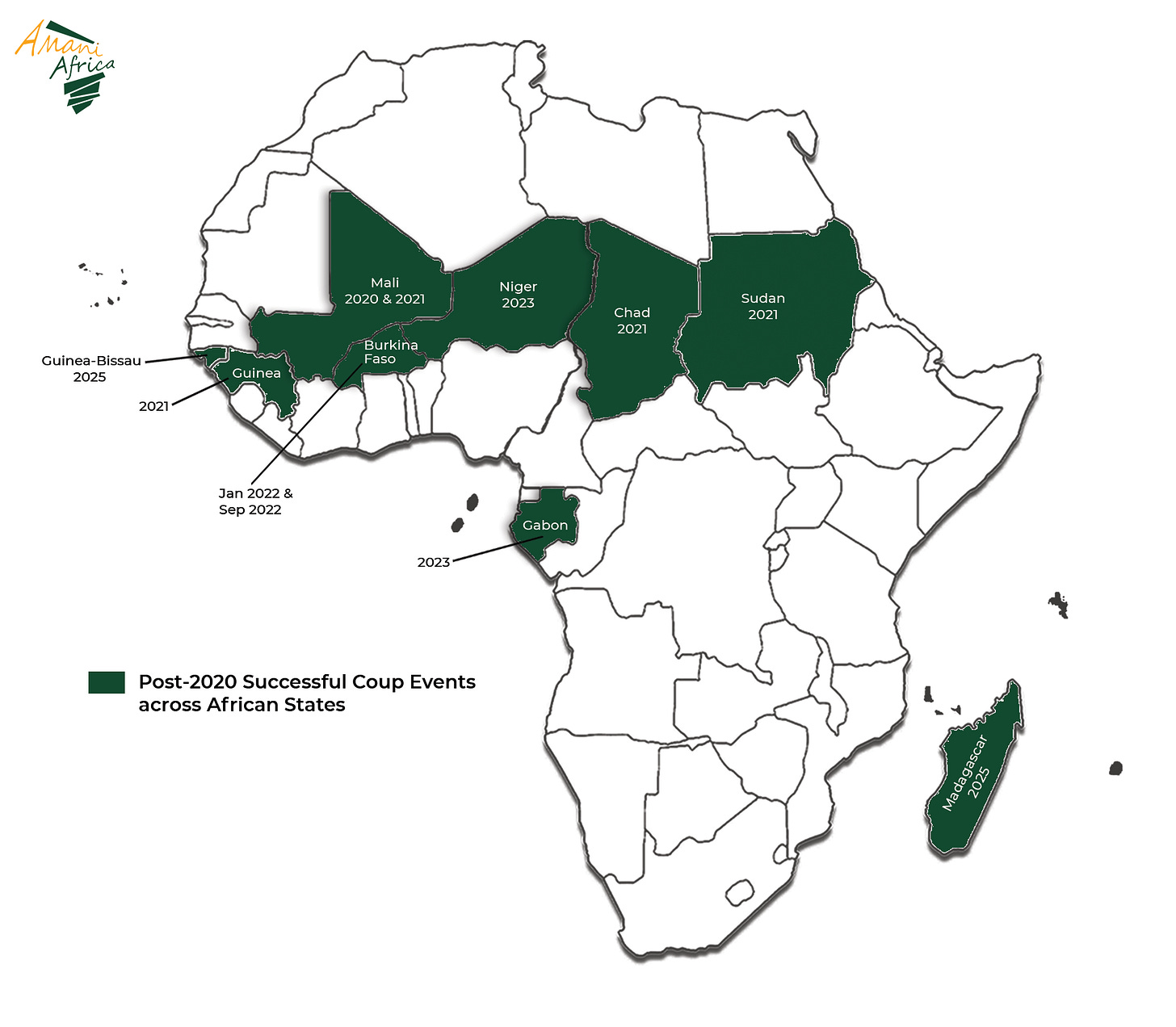

After a period of decline, there has been a noticeable uptick in the number of military coups in Africa primarily but not exclusively in former French colonies within the long stretch of territory commonly referred to as the Sahel. This trend is linked to factors such as state fragility, poor governance, the spread of violent insecurity and religious extremism, and citizen dissatisfaction with ineffective civilian governments that fail to deliver basic social goods and services.

In addition to a resurgence of military coups, “third-termism” (i.e. leaders attempting to extend their tenures beyond constitutional term limits), electoral manipulation, the entrenchment of civilian dictatorships and hereditary transitions as seen in Chad, Equatorial Guinea and Togo, have all hindered democratic consolidation on the continent.

Large majorities across Africa consistently express support for multiparty democracy and civilian-led governance. However, support for democratic ideals exists alongside significant dissatisfaction among African citizens with how democracy is practiced in their countries. Much of this disillusionment has led to growing support for military rule.

XXII. There has been an uptick in social mobilization across Africa including protests and social movements. Popular initiatives blend digital activism with in-person organizing, tackling issues from good governance, environmentalism, gender equality and police brutality.

Some notable examples of grassroots movements and social mobilization efforts include Le Balai Citoyen in Burkina Faso, #AllEyesonCongo in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Kenya’s Finance Bill Protests, End SARS and #EndBadGovernance demonstrations in Nigeria and #TasgutBas in Sudan.

Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter (X) and WhatsApp have become crucial tools for citizens—particularly youths—to circumvent traditional media censorship and control by the establishment in order to share information, hold discussions, amplify marginalized voices and participate in decentralized movements and protests.

Downsides to online-driven social mobilization include the rapid, extensive spread of false information and government repression via surveillance, censorship and lawfare.

XXIII. Africa has witnessed a sharp increase in armed violence since 2000, with the International Committee of the Red Cross stating last year that 40% of the world’s active conflicts are in Africa. Initiatives such as the AU’s ‘Silencing the Guns’ agenda have struggled to achieve their objectives of conflict prevention, management and resolution.

Extremist groups and armed militias capitalize on local grievances and weak state capacity in parts of the continent such as Eastern Congo, Libya, the Sahel and the Horn of Africa.

In West Africa, the continued involvement of the military and a resurgence of coups is closely associated with the rise of non-state armed groups.

XXIV. Issues such as social exclusion, economic marginalization, corruption, state fragility and the legacy of colonial-era borders drawn by Europeans continue to threaten cohesion, stability and sustainable development across Africa.

Many countries struggle with the implementation of effective governance reforms due to factors like the outsized, unrealistic demands on foreign donors and the entrenched nature of domestic institutional arrangements that are resistance to change.

Efforts at devolution and constitutional reform have had mixed results. Countries like Angola, Botswana, Kenya and Mozambique have implemented various processes of transferring governmental power, responsibilities and resources from central authorities to subnational bodies to varying degrees of success, as funding gaps, capacity issues and institutional quality have all affected the effectiveness of these reforms.

XXV. African leaders launched a restructuring of the continent’s institutional architecture, most notably with the transition from the Organization of African Unity (OAU) to the AU.

The overhaul, which is still ongoing in many ways, was an output of the “African solutions to African problems” mantra and reflected widespread agreement about the OAU’s shortcomings, which many believed hindered the organization’s effectiveness and made it ill-equipped to address the continent’s challenges in the 21st century.

The transition from the OAU to AU was notable for its increased focus on peace, security and governance. African leaders established several instruments that would support the AU’s broadened mandate including:

Official bodies such as the AU’s assembly of heads of state and government, executive council, Commission, the Pan-African Parliament and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights;

A Peace and Security Council tasked with promoting peace, security and stability in Africa and an African Standby Force that would deploy peace security operations to prevent, manage and help resolve crises.

The New Partnership for Africa’s Development, a socioeconomic development program that was created to enhance capacity building and project coordination among AU member states across sectors like infrastructure, health, education and climate change;

The African Peer Review Mechanism, a voluntary self-assessment tool for African states to review and assess governance issues, identify challenges and foster shared learning and best practices.

Continental integration has emerged as one of the AU’s core priorities as part of its ongoing institutional reforms and Agenda 2063 strategic framework.

The AU’s Constitutive Act prioritized relations between the organization and Africa’s eight Regional Economic Communities/Regional Mechanisms (RECs/RMs).

The AU identified the eight regional bodies as its “building blocks” tasked with driving regional economic and political integration, and the 2008 Protocol on Relations Between the African Union and Regional Economic Communities is the main protocol governing their cooperation.

Landmark initiatives such as the AfCFTA, the AU passport and the Single African Air Transport Market underscore the continent’s efforts toward greater integration and the creation of a “borderless” Africa.

The AU’s expanded remit has coincided with its growing prominence as an organ for Africa’s interactions on the global stage and many have praised its bigger mandate as ambitious

However, many others believe that the AU is beset by many if not most of the OAU’s shortfalls including the reluctance by African leaders to grant the organization more autonomy. Equally, the AU’s dependence on external donors and perception as a state-centric “dictators’ club” that shuts out civil society and the grassroots is regularly held up as one of its weaknesses.

As always in these pages, the use of “Sub-Saharan Africa” is purely referential. I don’t subscribe to the racist, ahistorical implication of the phrase.

Thank you for your contribution. I learned a lot.

Perhaps my analysis of economic development might interest you.

https://kappel1.substack.com/p/growth-without-transformation-in